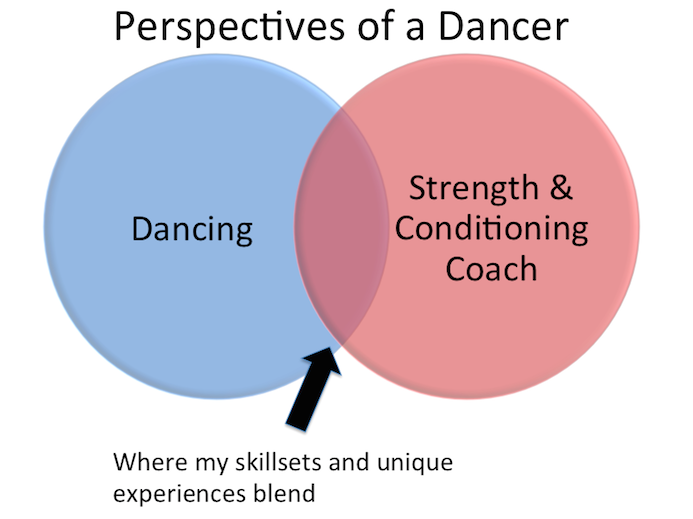

Dancing has painted the way I view many things in life. To the way I longingly look at any shiny floor in any part of the world (there were some dope places in London that I wanted to dance at… but security stopped me from doing so), to the way I choose the songs I casually listen to, to the way I even do my job of coaching athletes – my life is a canvas painted by dance.

What is probably the most interesting aspect of how dancing has infiltrated my work is how I coach the athletes and clients I work with on a daily basis.

Now, my unique blend of experiences and the way I view the world will shape how I approach exercise and essentially my job as a coach. Essentially, everyone will bring something unique to the table – this is what I bring.

The Tangibles

- For the athletes and clients I work with, I want you to move well, before moving with volume or heavy load.

- If you’re dancing, moving with a slower tempo before speeding up may be beneficial – or vice versa. Knowing when to slow it down and speed it up is crucial for success in both the dancing and strength & conditioning world.

- I want you to feel certain sensations as you do your exercises.

- From a coaching perspective, dancing has given me a different set of lenses that I use in order to convey different stories, analogies, and lessons to get across.

Long story short there are many benefits to dancing that I have transferred over at first, subconsciously from my experiences, but after seeing many coaches coach and do their thing, I began to realize this is where I’m different.

It is also an interesting story for others to hear – almost every other coach in the industry has a background that involves their high school and collegiate career in sports.

On the other hand, I openly admit to sucking at every organized sport pretty much my whole life, and knowing full well I wouldn’t be as good as my other friends, I decided to invest my time, energy, blood, sweat, and tears into dancing.

Intangible Skillsets That Transfer from Dancing to Coaching

1. Everything is a sensation

In dancing, the music drives the movement. In exercising, there is no attention to the music (other than just to hype you up).

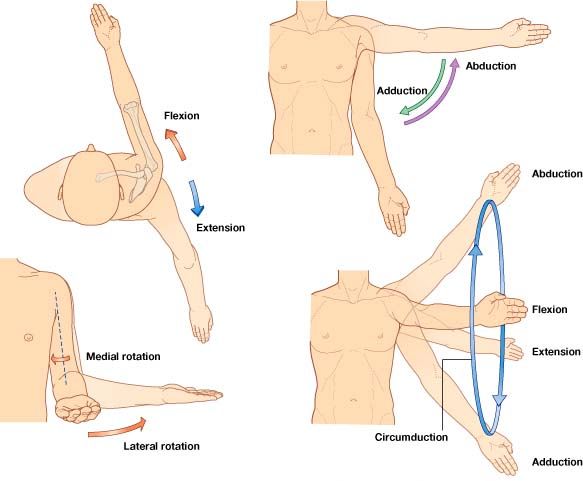

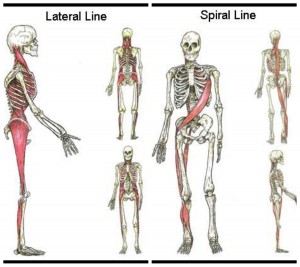

The takeaways that I’ve always used from dancing that help with coaching involve understanding that certain movements may “feel” a certain way in individuals – whether it is the right feeling or not is up for debate. In power moves in bboying, there is a certain “pulsing” that occurs when you are in the groove or in the correct position.

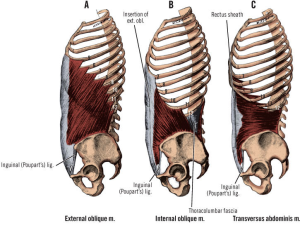

When exercising, if you aren’t feeling the correct areas being kicked on, my job as a coach is to help you feel those areas by any means necessary – with words, tools, stories, analogies, or by changing the exercise through a regression or other similar exercise.

2. Developing a “coach’s eye” through a different set of lenses.

Many have referenced the use of different ways to learn and coach – some learn by visual cueing, auditory, or even kinesthetic methods. I feel like I have developed my ability to deliver a high level kinesthetic coaching experience for anyone (certain populations aside of course).

See, my goals for getting you to move well involve efficiency and feeling. Being efficient means moving you into certain positions with as little verbiage as possible, without clogging your brain up with a bunch of things to think about.

For example, when teaching the basics to a squat to anyone, I really enjoy using the following strategies:

- Using a visual cue, using pointing when necessary to identify critical parts of the movement.

- Using an auditory cue simultaneously, such as “Knees go east and west of each other, as you squat to the box.”

- And finally, emphasizing a kinesthetic cue for an individual’s feet by pushing on the outside of their feet, and tapping their heels and likewise saying “Feel tension where I’m pushing.”

It’s never a singular sensorimotor experience that allows an individual to learn. If I can make you laugh, learn to breathe, and perform an exciting exercise they never thought possible, I’ve done my job. These are just a few items that emphasize the uniqueness that most dancers can bring to the table when coaching.

Actionable Items

If you’re a coach, what can you do to improve your ability to well… coach?!

1. Learn a new skillset.

For skillsets that involve movement, rhythm, and attention to detail, but still is lots of fun – I highly recommend salsa. Salsa is easy enough to learn from your micro-failures early on, that big takeaways can be learned right away from several YouTube videos, or if you’re daring enough at a salsa club or lessons.

(Word to the wise: Havana Club in Cambridge/Boston area has lessons an hour before they have the full blown salsa night. Check it out if you’re in the area. Oh, and hit me up if you plan on going as well! :) )

Learning a new skill such as this will expose you (the coach) to the feelings of being a novice all over again. It is surprising, but many coaches may stick to their strengths out of fear of being exposed, or even clinging to the thought of looking dumb. Just think of how your athletes feel when you try to have them do anything new.

By walking (dancing) a mile in their shoes, you can re-experience what it means to learn a new skill set all over again, which may give you better perspective and experience to help ease your athletes or clients’ worries.

And, it doesn’t have to be salsa. It can be learning the intricacies of a new sport, learning a new set of recipes to cook, or just simply stepping outside your comfort levels for an hour or so out of the week!

Learning a new skill set also gives you a broader vocabulary with which to convey your intentions as a coach. If I want my athlete’s body to remain as still as possible, and perform a specific exercise that may require movement of only one or two body parts, I’ll ask them to stay still like they are doing the robot, but then move this part (pointing or demonstrating) only. If they have no idea what “the robot” is, then I can show them right then and there – they laugh, I laugh, they do the exercise – gains.

2. Learn the rhythm to every exercise.

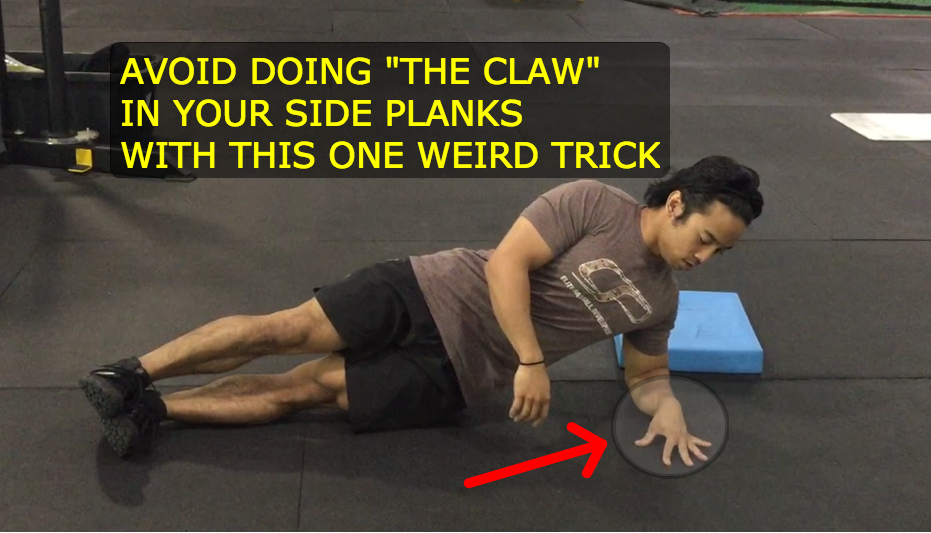

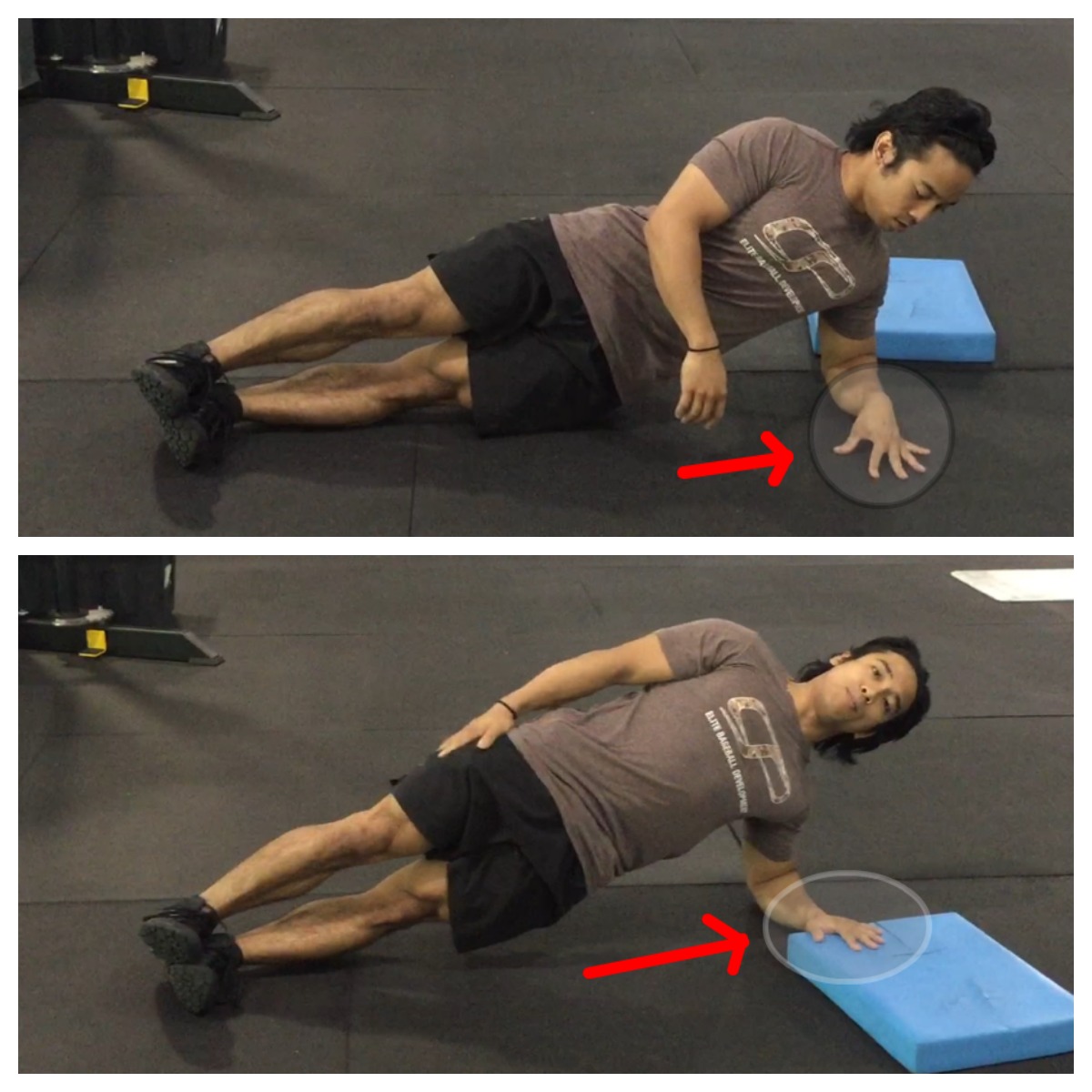

Every exercise has a rhythm – yes even stationary exercises such as planks and side planks. (If you remember to breathe during these static drills, you can see what I’m talking about.)

Other than the obvious rhythmic exercises such as kettlebell swings, sprints, or skips, exercises such as squats, deadlifts, hang cleans, and medicine ball drills all have specific rhythms to adhere to achieve success.

- With KB Swings, there is a portion where your torso is parallel-ish to the floor, and then a moment of weightlessness as the KB accelerates away from your hips (and your lower half shoulder feel like it goes down into the ground).

- With sprints there is a moment of speed and pulsing that is created when you move past the acceleration phase.

- With squats, there is a bouncy feeling that you need coming out of the hole while maintaining a tall torso position, at least for the intermediate to advanced lifters.

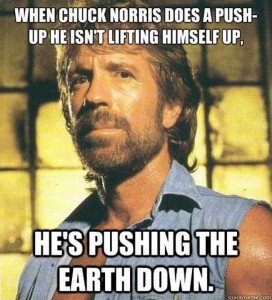

- With push-ups, there should be a feeling of pushing the earth away ala Chuck Norris jokes from 2005.

See if you can find the rhythms in other exercises, and use whatever verbiage (or kinesthetic cues) you can to describe it to help you coach these exercises better.

I personally use powerful words to help describe the intensity in these movements – with KB Swings there is an early “snap” out of the hips that helps to improve your movement, with medicine ball slams there is a “boom” that also facilitates intensity.

As you can see, there are tons of different perspectives that allow myself, a dancer turned strength coach, to be successful in a room full of otherwise very sports minded individuals.

One thing to keep in mind is that many of the above items refer to biomechanical and neurological sensations as a key towards unlocking movement success. For the athletes and clients I work with, this is not to underestimate their ability to attain certain physiological adaptations as well. They are connected, but not the same. At the same time, please don’t believe that every item I perform involves stretching to the max – I believe in having flexible and pliable muscles, but that is not usually my end goal for you as the client or athlete!

There is a certainly a time and place for everything, this is simply my own take on it!

As always,

Keep it funky.