What is The 90/90 Hip Lift?

The 90/90 Hip Lift is an integral and foundational exercise from the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI). It is often taught in the foundational courses from PRI, and it is often where many clients, patients, and athletes begin their PRI journey. As a practitioner, I find myself coming back to this piece quite often, as it allows me to see an individual’s motor control in many specific areas and more.

The 90/90 Hip Lift is an exercise that begins in a supine position (on your back), with your feet on an elevated surface, and knees in a flexed (or bent) position.

Sometimes you can have something in between your knees, other times not. The following article will describe more beyond just the initial position. The execution of this movement may be the most underrated aspect of this exercise, as a well executed 90/90 Hip Lift can help teach foundational lessons for further exploration later on.

Background for Using This Exercise

There are lots of reasons why someone might want to use this exercise. Reasons may involve relieving a certain region of sensory pain, improving sensory awareness of the body, and perhaps improving injuries that are often re-occurring. More specifically, the science of postural asymmetry and its effect on the body is evidenced from the Postural Restoration Institute’s multi-disciplinary approach.

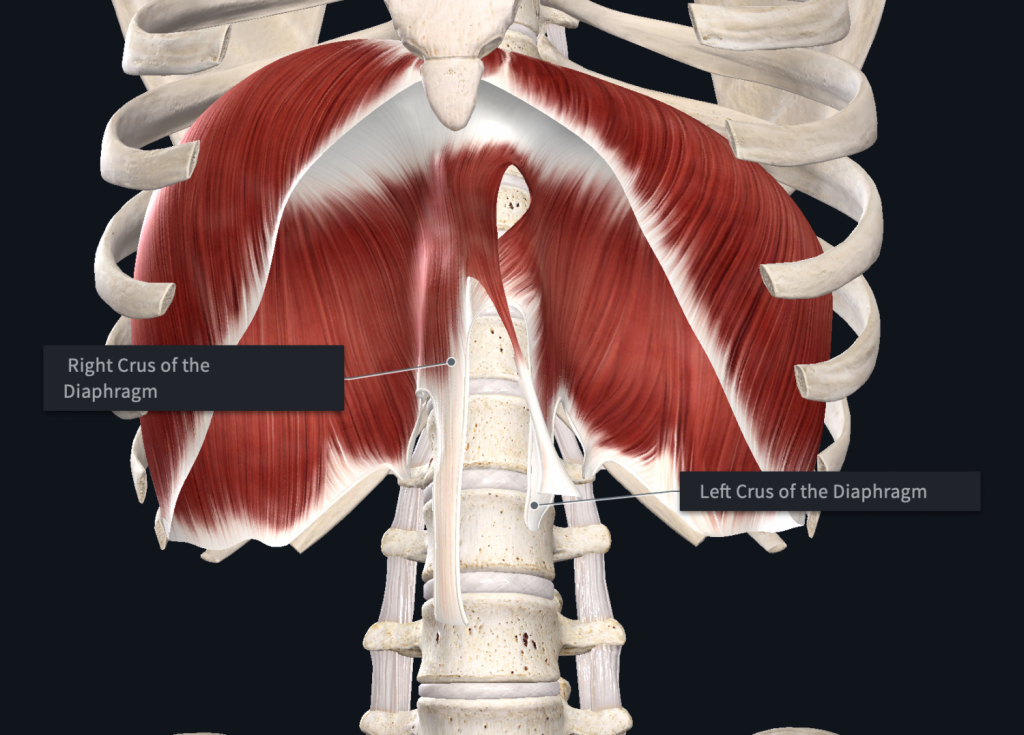

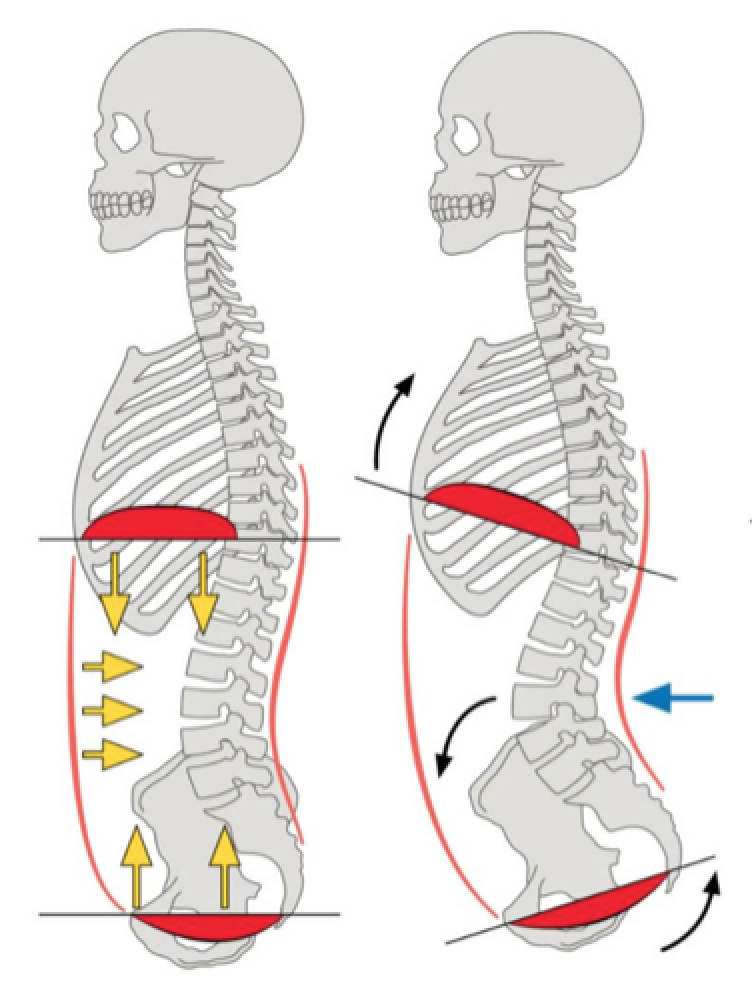

At the end of the day, there are several internal and structural asymmetries that are present in the human body, along with hemispheric (or brain) asymmetries that can dictate varying function of the body. For example, there is a liver on the right side of the body, and the heart on the upper left side of the chest wall. Further, there are different attachments of the diaphragm, with the right crus of the diaphragm being stronger, broader and longer than the left diaphragm.

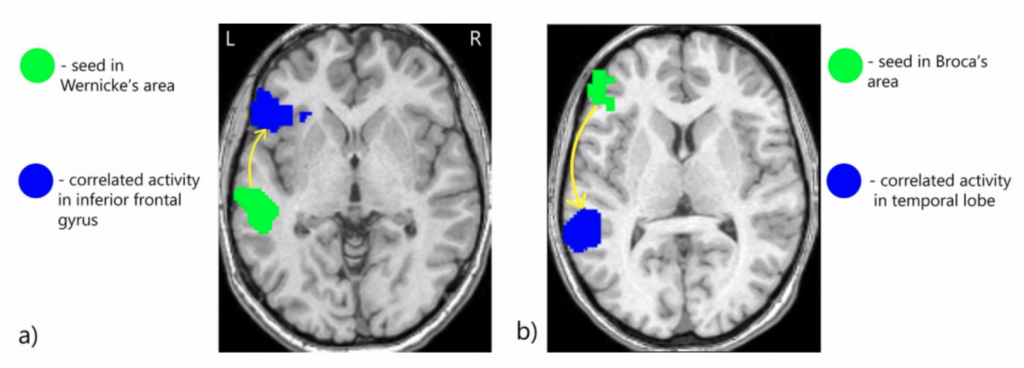

In the brain, there are different structures that are more neurologically active in the right vs left hemispheres. For example, Broca’s and Wernicke’s area are found in the left hemisphere for language production, but not in the right hemisphere. This has a great impact on asymmetry for communication and interpretation of language. (1)

With this said, the purpose of varying movements isn’t necessarily to “eliminate” any asymmetries as a cause of this and be as perfectly symmetrical as possible, because this would need for you to move your heart, liver, re-arrange your physical brain, along with removing other key body parts, but rather understand and acknowledge the body’s asymmetry with respect to performance on a daily or competitive level.

From a clinical perspective, I find myself utilizing the 90/90 Hip Lift from a foundational perspective, as it is often the first position that is introduced from a motor control position:

- It’s easier to learn finer detailed movements, and adapt them from this position

- You can change multiple positions of limbs, such as legs in adduction/internal rotation or the opposite leg in abduction/external rotation, while still being in the base 90/90 Hip Lift position

- It’s perhaps easier to feel and sense muscles activating

- It allows you to focus on breathing as well

Often I may progress from this 90/90 Hip Lift position to sidelying, seated, or even progressing to standing if it is necessary to do so.

Populations that May Benefit:

- Athletes

- Individuals who are placed into chronic positions (due to work, constant standing, etc.)

- Anyone looking to improve upon their body’s musculature, particularly the hamstrings, abdominals, and gluteals

- Populations that find themselves “neurologically stuck” in an extended posture bilaterally

- Individuals who experience further symptoms secondary (or because of) a tight lower back, anterior hip pinching during squatting, or even hip discomfort during lunging, among other things

- Individuals who display excessive hip or femoral external rotation (barring osteo- or bony adaptations), and are looking to improve hip internal rotation values

Instructions for the 90/90 Hip Lift

From the PRI manual verbatim

- Lie on your back with your feet flat on a wall and your knees and hips bent at a 90- degree angle.

- Place a 4-6 inch ball between your knees.

- Inhale through your nose and exhale through your mouth, performing a pelvic tilt so that your tailbone is raised slightly off the mat.

- Keep your back flat on the mat. Do not press your feet into the wall, instead dig down with your heels. You should feel the muscles on the back of your thighs engage.

- Hold this position while you take 4-5 deep breaths, in through your nose and out through your mouth.

- Relax and repeat 4 more times.

Understanding and Executing the 90/90 Hip Lift

It is my hope that if anything, you stick to the “algorithm” if you aren’t comfortable moving beyond this level. However, this is my site, and I’d like to provide you with my interpretation of how to improve your execution of the 90/90 Hip Lift.

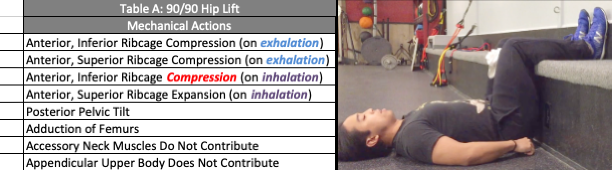

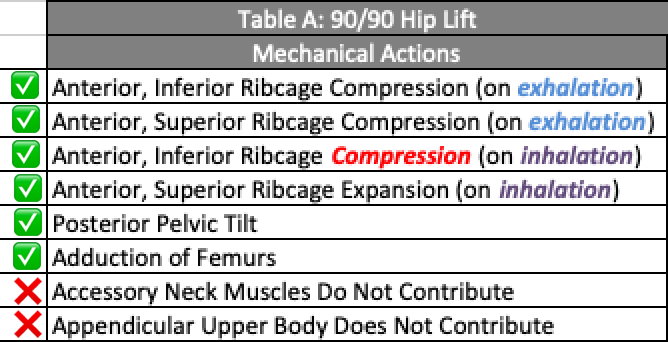

With Table A, there are 8 pieces that essentially need to take place before moving on. If they don’t take place, can you really say you’ve achieved authentic muscular contractions in the correct manner?

- Can you say you’ve achieved a posterior pelvic tilt, if indeed you haven’t achieved a posterior pelvic tilt without the hamstrings and obliques?

- Can you say you’ve achieved compression of the anterior superior and inferior ribcage if you haven’t inhibited the pectoralis major/minor, and utilized the obliques and serratus anterior attachment on the ribcage?

- Can you say you’ve achieved an appropriate zone of apposition if you use accessory neck musculature to help with breathing, instead of the abdominals, thoracic diaphragm, and pelvic diaphragm?

Now, with the process of troubleshooting, it is definitely okay to miss key elements, because that is the point – you haven’t learned the whole movement, so you’ll be acquiring one piece at a time. It may in fact take 5-10 minutes (or even days, weeks, or months!) to teach the sensation of what posterior pelvic tilt means without using any musculature that does not contribute, for example.

One key item to not overlook is the bolded red mechanical action of ribcage compression on inhalation – the reason being that you don’t want your ribcage to flare and expand upon inhalation, when you just achieved your position. This effectively loses the mechanical advantage that your internal obliques have on your ribcage and pelvis, along with utilizing the diaphragm to help improve upon thoracolumbar and ribcage positioning … which is the whole point of the exercise.

At the end of the day, learning the 90/90 Hip Lift will set the stage for greater stacking as we progress towards the 90/90 Hip Shift, and 90/90 Hip Shift with Integration.

So, if you only have 12.5% of Table A, that is fine, as long as you progress towards 25% the next time you practice it, then onwards to 37.5% while also retaining the original first piece to this puzzle in the process.

Cueing and Attention

A common denominator among many of these PRI activities is the attention to detail found in the movement itself, along with the execution of these exercises from the athlete’s perspective.

When you have an activity that requires attention in more than one area, such as acquiring and maintaining sensation in hamstrings (back of your legs) and adductors (medial aspect of your legs) simultaneously, it quickly becomes apparent that some level of interoception, or a lesser-known sense that helps you understand and feel what’s going on inside your body, is necessary. However, as a coach, how do you prioritize which piece of the movement to coach? How do you allow for ease of understanding? Is interoception detrimental towards performance (similar to internal attentional focus)?

Something familiar for coaches to recognize and coach is a back squat. At the end of the day, it is simple. It involves a level change (standing tall to sitting down) with a fixed torso (that does not fold nor bends during the movement), and there happens to be a barbell on your back. Initially it is as easy as that, but then eventually you’ll need to pay attention to:

- Hand position

- High bar vs low bar

- Foot width and position

- Intra-abdominal pressure

- Visual gaze

… among many other nuances found in a wide variety of successful squatting.

However, despite all of these individual pieces that can be fine tuned in the back squat, how can any individual successfully back squat when there can be anywhere from 5 to 8 items to pay attention to in the squat?

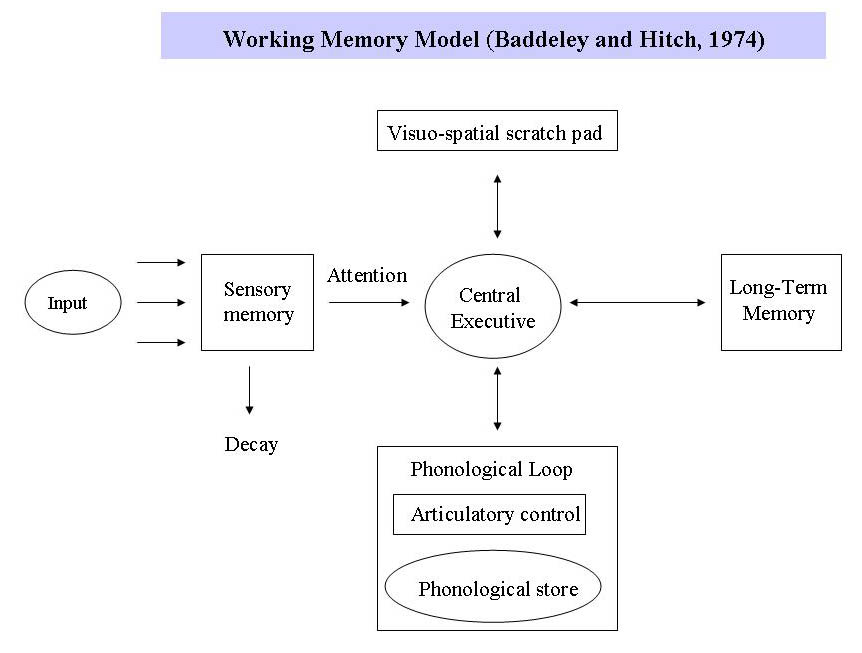

This answer lies in the sensory processing and motor output associated with different movements and is analogously related to how the 90/90 Hip Lift can progress and advance beyond its simplistic nature.

Understanding Sensation and Sensory Processing

“… The nervous system extracts only certain pieces of information from each stimulus while ignoring others… Thus, we receive electromagnetic waves of different frequencies, but we see them as colors… Colors, tones, smells, and tastes are mental creations constructed by the brain out of sensory experience. They do not exist as such outside of the brain.”

(Kandel et al.) (3)

Writing a whole bit on perception in less than a paragraph would be a disservice since there are literally books upon books on the topic, so I’ll save that document for another 3000+ (or multiple articles) word article. However, understanding how the perceptual system is developed as you grow and experience more and more things in your life is important. The things you feel, smell, hear, see, and taste are all important factors for helping you do several things – mainly, to learn about and navigate your environment.

In the field of strength and conditioning, the practice of improving upon the sensitivity of how sports specific movement is practiced, trained, retained, and transferred is just beginning. Meanwhile, the field of motor control and motor learning has been thriving for many years. An important topic within motor control is “attention of focus” – and it splits into two distinct definitions of internal and external attention of focus. Colloquially, it is known as internal and external cueing.

Internal attention of focus is directed toward components of the body movement, whereas interoception’s definition and scope of use “ranges from the sense of agency, to the physical cause of a sensation, the ontogenetic origin, the efferent innervation, and afferent pathways of the tissue involved amongst others.” (4)

These are two vastly different meanings, as sense of agency has implications into the developmental processes of an individual. During instruction, if the practitioner or coach delivers internal cueing as a method for feedback, there is a high price in describing the processes involved with your body, namely a reduction in performance. (5) (6)

However, what happens if there is no concept of what your knee is, or what your hamstrings look like, or what your body is doing from a proprioception point of view? (7) Can you even begin to conceptualize what body parts you are being cued to pay attention to if you aren’t aware that you have different body parts to begin with?

Motor learning can arrive through several means. In this particular type of exercise, motor learning is encouraged by…

- Being cognizant of a sensation,

- Shifting that sensation into the subconsciousness without losing the output of the said sensation,

- And then carrying onwards to another integrated movement (with greater complexity).

Image from Simply Psychology – Working Memory

For example, in the 90/90 Hip Lift:

- You may become acutely aware of your hamstrings during the posterior pelvic tilt as your first step.

- Then, you decide to move onwards to your abdominals and ribcage compression during exhalation.

- During this, you may lose sensation of your hamstrings, but finally achieve the sensation of “tightness” in your abdominals during exhalation.

- Afterwards, your goal is achieve both sensation of your hamstrings and your abdominals simultaneously.

Ta-da! You’ve completed a 90/90 Hip Lift successfully.

How do you feel?

In Review…

- There are inherent structural asymmetries present in the body.

- Before tuning your body to these asymmetries and its impact on the musculoskeletal system, understanding the base position of the 90/90 Hip Lift is necessary before continuing towards advanced activities.

- If you achieve one out of the eight pieces found Table A, that is fine, so long as you own and retain that without any other compensations.

- The next step is to attain a second piece (in addition to the first piece).

- Then, your next step is to sense and obtain the third piece, while still actively holding all of the other pieces.

- And finally, obtain the fourth piece, while still actively holding all of the other pieces.

- The bigger purpose is to move in one whole pattern, instead of sequentially acquiring each piece.

- Sensory processing is integral towards improving the motor output.

- Interoception is different than internal attention of focus.

Now, this sounds like a big endeavor when it is laid out like this, and that is the point.

Attempting to achieve integration of many pieces is the goal. When it comes to sensing your own body, you’ll often find that certain sensations will fade in and out of your awareness – which is the point. For example, conscious and subconscious perception allows you to sit and stand where you are without being cognitively aware of these surroundings, but cognitive sensation of these sources of stability may be brought to mid if you feel unease or maybe slip while you walk.

The purpose of the 90/90 Hip Lift, 90/90 Hip Shift, and many other exercises within this realm, are to improve upon how you sense your own body before creating a greater task for motor output throughout your environment.

Stay tuned for the next article, where I’ll go over what the 90/90 Hip Shift covers and how to properly execute it.

As always,

Keep it funky.

References

1 – Toga, A., Thompson, P. Mapping brain asymmetry. Nat Rev Neurosci 4, 37–48 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1009

2 – Makovskaya, Lyudmila, et al. “Localization of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas with resting state fMRI.” European Congress of Radiology 2016, 2016.

3 – Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics Thomas Jessell, Steven Siegelbaum, and A. J. Hudspeth. Principles of neural science. Eds. Eric R. Kandel, James H. Schwartz, and Thomas M. Jessell. Vol. 4. New York: McGraw-hill, 2000.

4 – Schmitt, Daniel. “Insights into the evolution of human bipedalism from experimental studies of humans and other primates.” Journal of Experimental Biology 206.9 (2003): 1437-1448.

5 – Zachry, Tiffany, et al. “Increased movement accuracy and reduced EMG activity as the result of adopting an external focus of attention.” Brain research bulletin 67.4 (2005): 304-309.

6 – Wulf, Gabriele, Barbara Lauterbach, and Tonya Toole. “The learning advantages of an external focus of attention in golf.” Research quarterly for exercise and sport 70.2 (1999): 120-126.APA

7 – Kuo, Arthur D. “An optimal state estimation model of sensory integration in human postural balance.” Journal of neural engineering 2.3 (2005): S235.

Pingback: The 90/90 Hip Shift with Alternating Crossover - MiguelAragoncillo.com