In the US, just about every professional, college spring season, and high school spring season sport are cancelled. In the meantime, strength coaches, performance coaches, and trainers across the nation (and world) are maybe left out of work, or have scrambled in the recent weeks to create workouts for athletes to perform at home with no equipment, or limited equipment. With this article, I will be going over how to approach exercise programming when every sport is cancelled or shutdown.

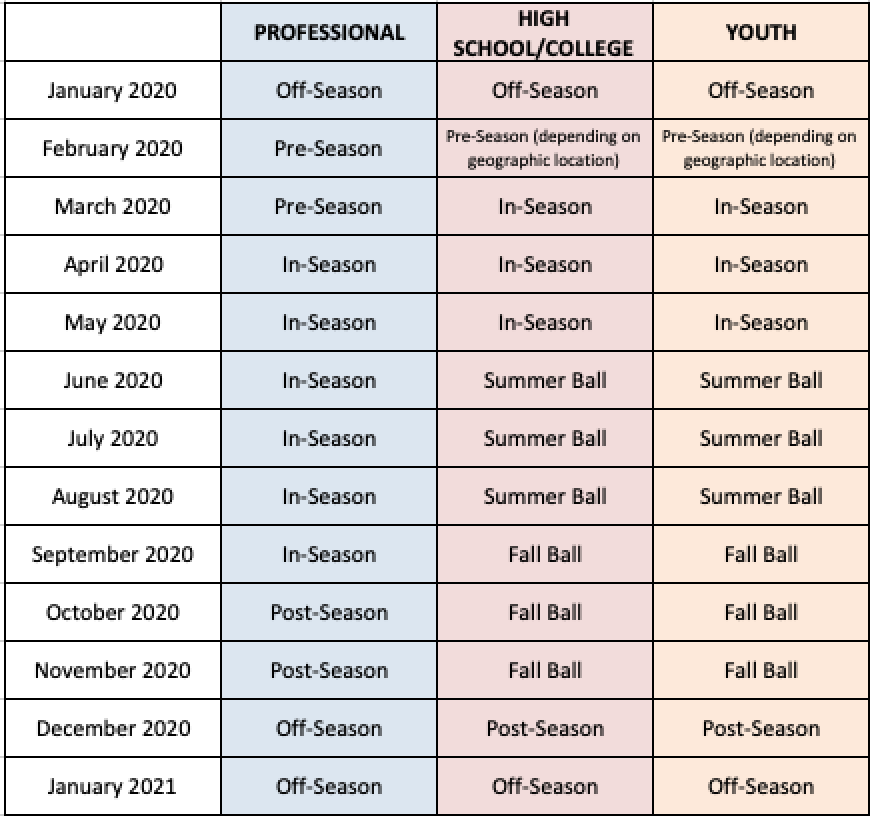

When it comes down to creating programs for sports, there is often time, energy, and attention paid towards certain blocks during any given calendar year: the off-season, pre-season, in-season, and post-season.

During the off-season, there are a number of adaptations, based on the sports demands and individual demands of certain positions, that are often trained to allow an individual to express capacity in their sport, along with the capacity for training sports specific movements.

In baseball, there is often a desire for increasing force production for short bursts of explosive power demonstrated in several movements (pitching, hitting, sprinting). In soccer there is often a desire for increased aerobic endurance, which helps to sustain energy system demands for the sport, but also to improve upon how the body will recover in between bouts of sprinting.

No matter the sport, there will be often be certain desires for one (or a few) specific enhancement(s) of a physiological quality over another, and with that, there will come with it a subsequent focus in exercise programming.

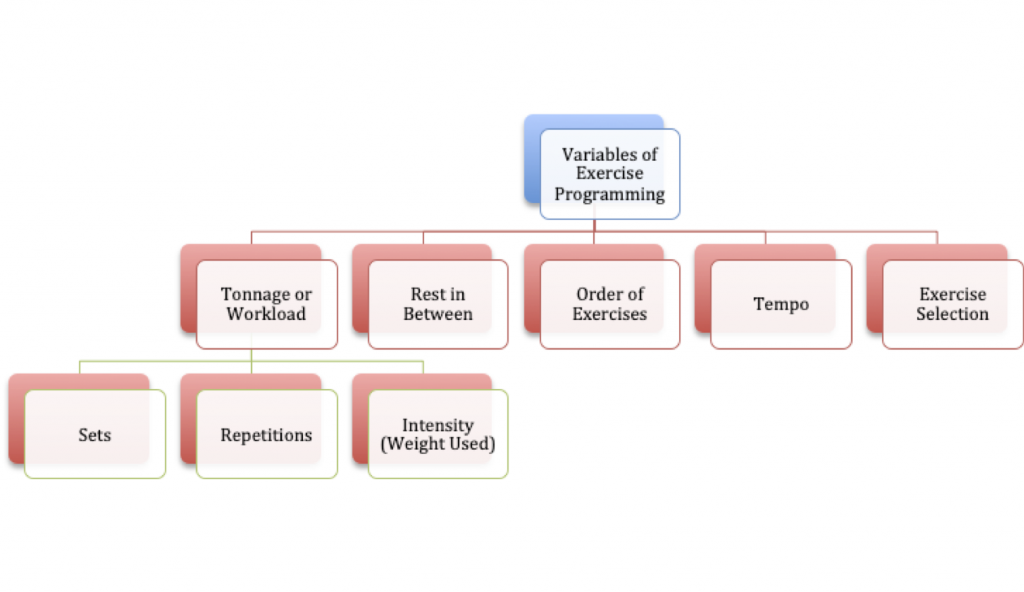

Different sorts of exercise programming will dictate different sets, reps and then different exercise sets, repetitions, and rest times in between. These, among other variables, will dictate the intensity levels that are experienced by the athlete who is exercising.

But what happens when there is an interruption to training, much like the extended off-season many spring sport athletes are experiencing now?

Changes or Interruptions to Your In-Season

If approached correctly, the off-season is a time where an athlete can build capacity, improve neuromuscular strength, hypertrophy, and perhaps speed and power as well.

With the in-season, depending on how long your season may be, some of these physiological qualities may see a decrease in quantitative values. Meaning, from a maximal strength perspective, there may be a decrease in the RM value in various exercises that were previously trained during the off-season. Further, since speed qualities are more representative of the sporting demands that take place during competition, these speed qualities often aren’t lost as much.

However, there is now an increase in time that athletes may be experiencing in their off-season now. Spring athletes may not get to play until the fall (or summer ball, depending on the sport/dates of re-opening).

With this said, I see a few reasons to also re-focus the training focus for athletes that may have been in season. These changes, depending on the needs of the individual, include more cardiovascular programming options within an athlete’s program; especially with this long break of an off-season that almost everyone is experiencing.

What Do Athletes Do Now?

Chances are if you’re a high school, college, or even professional athlete, you may not have access to all the weights found in a normal gym. Coupled with the fact that your normal spring sport is very likely cancelled, and the fact that most gyms are closed (or perhaps on the way to being re-opened), the ability for you to train with weights may be limited. So pragmatically, you have these variables to deal with:

- None or limited weights.

- Extra time to train other qualities that are usually not developed due to competitive demands.

Your normal phases of training during the year is usually defined as such:

Now, your training may look like this:

So what do you do now that you have over 4+ months of another off-season? Do you call it quits? Do you just stop training? Do you play Fortnite and Call of Duty instead?

Introducing Cardiovascular Training

What you can do is train in several ways not normally encouraged due to the limitations with a < 2 month window for an off-season.

If you have one block for each month of training, you can certainly induce some great benefits for yourself not just this year, but to support your training in the future.

Now, if you’re within the strength and conditioning industry, these methods should not be any surprise to you. Joel Jamieson introduced a few of these methods to the S&C world, and some methods have been around for many years before then. However, Joel Jamieson was an individual who has re-tooled these methods in a more easily understood manner, along with having a greater scientific reasoning for doing so.

Reasons for Training the Cardiovascular System for an Explosive Athlete

Training the cardiovascular system can allow for greater volumes of training to be experienced later on in the off-season.

For example, if you do these sorts of training now, you’re likely to induce greater benefits to the cardiovascular system.

Then, the hope is, these benefits will likely carry over later towards another block of training found in later, subsequent training blocks.

Utilizing Cardiovascular Training in a Strength and Power Block

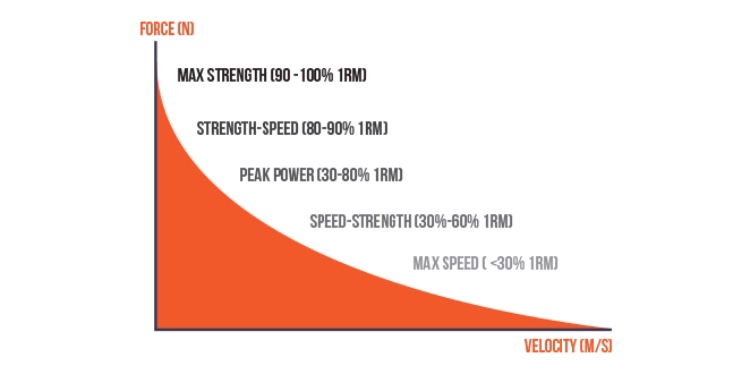

Many subscribe to the notion that doing any type of cardiovascular work will detract from strength and power gains. Some research identified that there were decreases in forces at high velocities (think jumping for max distance) (2), but it helps to pay attention to what the original research was looking at – muscle fibers shifting to adapt towards greater oxygen demanding activities.

This reasoning makes sense, however, the purpose of training the cardiovascular system to improve efficiency of recovery, and increase potential tonnage of training along a 6-12 month timeline is not really addressed in any study.

With respect to studies, there is no greater “self-experiment” for athletes to impose cardiovascular adaptations on themselves than today, in which there has been, for the most part, a large quarantine (or stay-at-home) order in many states in the US. (At the time of this article, some orders are easing this order.)

Benefits can include greater adaptation in your heart, so that you can support greater amounts of volume. The way this occurs is by allowing your aerobic system to restore and allow for your heart rate to return to normal at a quicker rate. This is opposed to if you did not do any cardiovascular work, and your heart rate takes longer to return to a normalized resting level.

Measuring Progress for Cardiovascular Adaptations

So for example, say during a typical training session, your heart rate is pumping at a high rate (160-180+ bpm). Then, it takes a while for you to recover after a given bout of exercise (longer than 1 minute to return to 130bpm, for example).

After performing 3-5 weeks of a given endurance block (in addition to your original strength training sessions), that same bout of exercise brings you to 160-180+bpm, but then it takes you less than 1 minute to return to 130bpm, this indicates that your heart has adapted, and your cardiovascular system recovers faster than before.

Another method for measuring progress is to train for a given time (30, 60, or 90min), often with a sustained, activity with no breaks, and then attempt to push further in distance, or have a reduction in intensity levels while still maintaining the distance attained.

These may indicate more work is performed, while the cardiovascular adaptations are realized as well. For example:

- It may take you 30 minutes to run 2 miles on Week 1, at an average heart rate of 160bpm.

- Then, fast forward to Week 5 or 6, and you’re performing 2.5 or even 2.75 miles in 30 minutes with an average heart rate of 145-150bpm.

This means you are most definitely performing more work within the given time frame, or even the same amount of work with a reduced amount of intensity! All of these things mean you may be getting more efficient from a cardiovascular perspective.

Another method of identifying progress, now in the context of weight lifting, is to do simply do more work and having more volume for a given training block. By doing this, you’ll be able to create greater adaptations, because there is a greater stress induced on your system. For example:

- Week 1: Back Squat – 3×10 reps with 120-150sec rest

- HR average is at 170

Then on Week 6…

- Week 6: Back Squat – 3×10 reps with 90-120sec rest

- HR average is at 160

You’ll no longer be stressed as much by doing the same sets and reps as , and performing it at a certain weight will also not be as stressful. This indicates your body has adapted, is more efficient, and may need an adjustment of a variable for training – such as increase in weights, less rest time in between sets, or more sets and reps overall.

Programming Methods for Cardiovascular Adaptations

With all these reasons outlined, it would now help to understand how to program these methods to best experience these results.

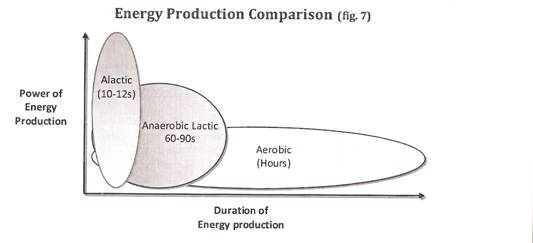

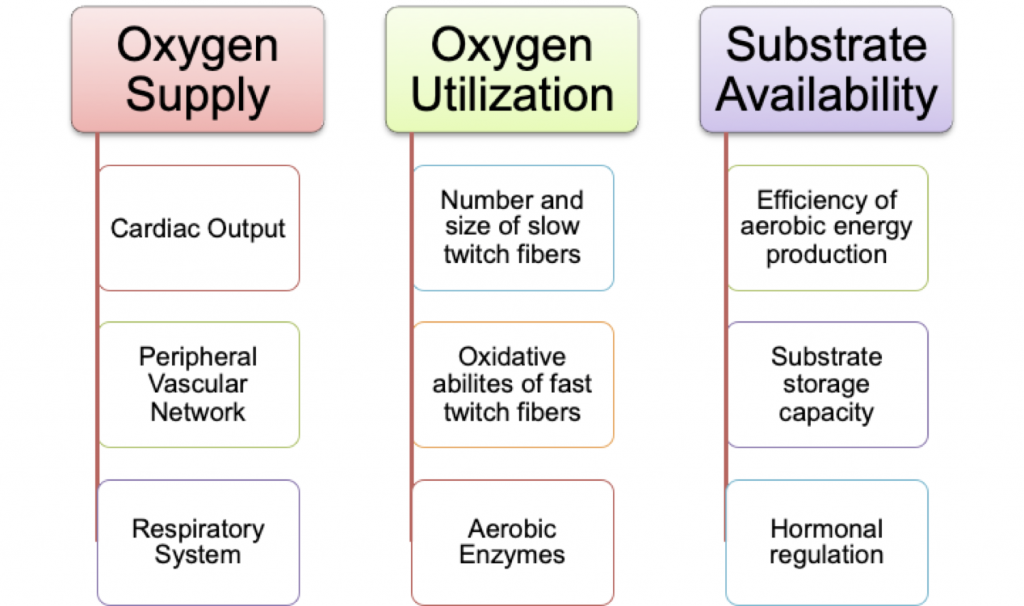

From an energy systems training perspective, there are a few reasons why an athlete would want to improve both their cardiovascular and neuromuscular system.

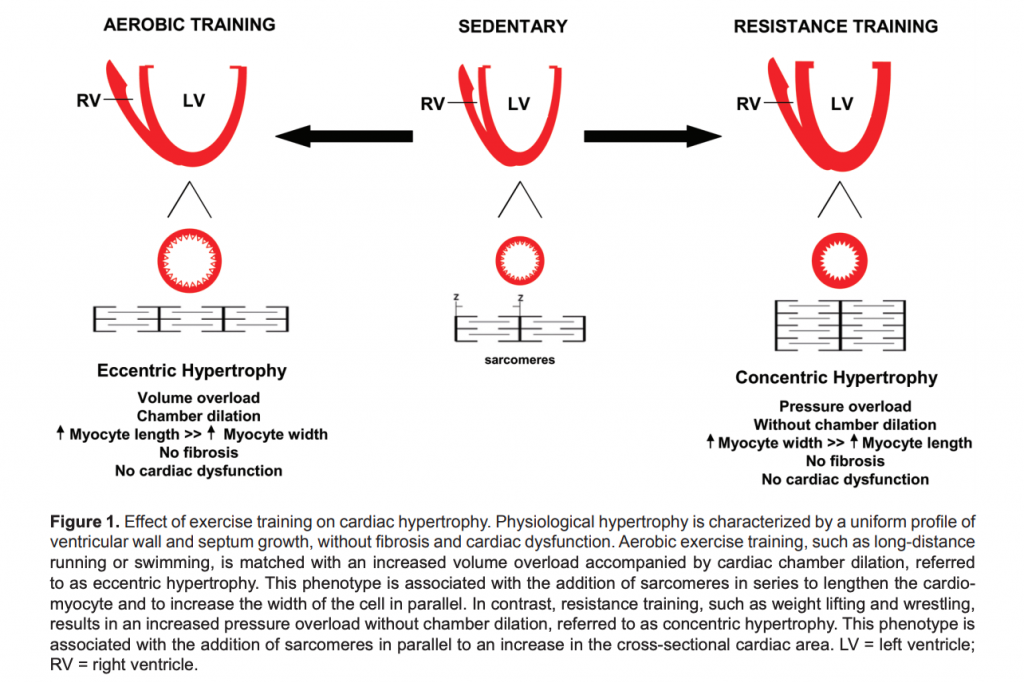

- If an athlete can improve the functioning of their heart via eccentric hypertrophy, this will allow for a larger chamber with which the blood can fill the heart, along with improving the contractility of the heart.

- Focusing on improving development of the slow twitch fibers by utilizing oxygen within the working muscles.

- Improvements in fast twitch fibers, which will enable them to generate ATP for much longer before fatiguing.

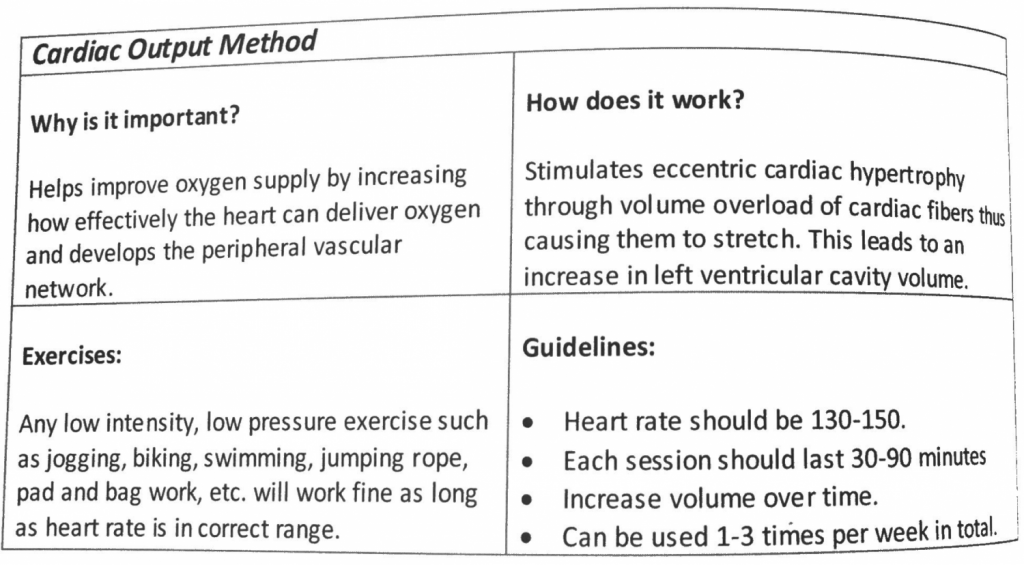

Cardiac Output

The cardiac output method is considered high volume/low intensity, and is perhaps the easiest to perform out of all of the methods I’ve outlined so far. In essence, the purpose is to perform something relatively easy for 30-90 minutes at a time. Performed for multiple times over several weeks, this will eventually improve upon the cardiac benefits that I’ve outlined above.

Low Box Step Ups – Cardiac Output Method

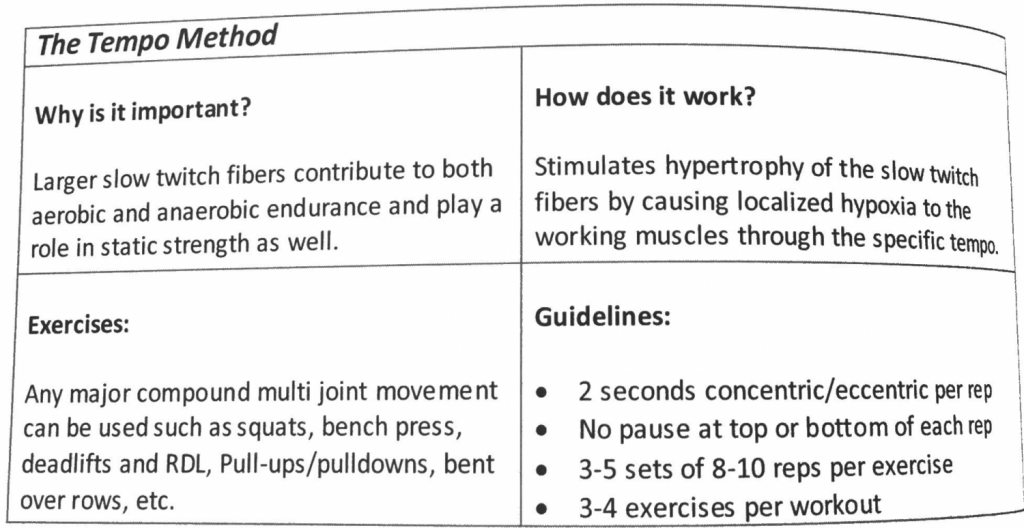

Tempo Method

The tempo method is one that I’ve used with great success with athletes aiming to improve their weight lifting numbers. Yes, this is primarily an article on cardiovascular benefits and adaptations, but holding a relatively heavy weight for a certain amount of reps under a strict tempo is bound to stress the nervous system, as well. For example, I’ve had athletes perform trap bar deadlifts with a 2-0-2 (or 2 seconds up, no stopping at the bottom, and 2 seconds down) for 6-8 reps. That alone sounds miserable – but it is effective for improving motor control (no loss of upper body position should be had here), along with improving grip strength (unless you are using straps). This can either be brutal, or sneakily effective – depending on how you want to use it.

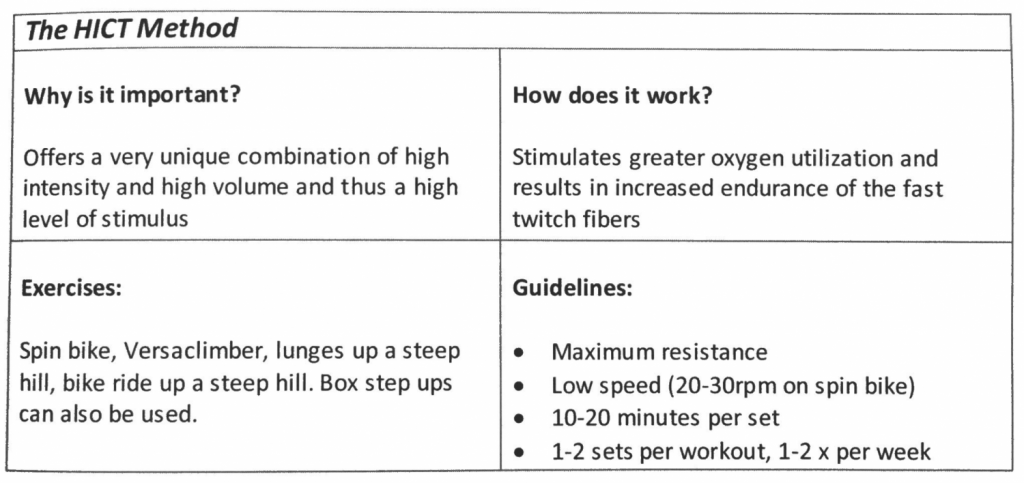

High Intensity Continuous Training (HICT)

This is easily one of the harder variations of training that is outlined in this article. I’ve experimented with this myself, and then transferred it to some athletes as well, and the experience alone is demanding but doable. Performing sled pushes, drags, or lunges with a weight vest for 10-20 min is brutal, and you’ll certainly feel it the next day or two. However, the benefits are truly amazing, as reduction in heart rate in comparison to previous efforts (doing the first week of HICT’s loading and timing parameters again, after completing a 2nd or 3rd week, for example) is seen here, which is amazing to think about.

Then, from a week to week and exercise selection perspective for the next 6 weeks, your cardiovascular training (in addition to your normal strength training, if accessible), can look like…

Week 1+2 = Cardiac Output

- Low Box Step Ups

- Walking Forward Lunges (Bodyweight)

- Stationary Bicycle / AirDyne

- Jogging

- Shuttle Runs (at 130-150 HR)

- Walking with Weight Vest

Week 3+4 = Tempo Method

- Any compound exercise

Week 5+6 = HICT

- Sled Drag

- Sled Push

- Stationary Bicycle/AirDyne at High Resistance

- Rowing/Erg at High Resistance

- Lunges with Weight Vest

Improving the cardiovascular system’s efficiency, oxygen utilization, and increased ability to recover is important for expressing physical preparedness, especially when it comes to sports specific training.

Further, by prefacing your traditional strength block of training during the off-season with these improvements to your cardiovascular system, you’ll be more able to increase tonnage (sets x reps x weight used) for training, along with having an easier time to recover in between sets.

So, hopefully you take these elements into account before continuing with your exercise programming, next HIIT class, or video call made to only make you sweat.

As always,

Keep it funky.

MA

References

1 – Fernandes, T., U. P. R. Soci, and E. M. Oliveira. “Eccentric and concentric cardiac hypertrophy induced by exercise training: microRNAs and molecular determinants.” Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 44.9 (2011): 836-847.

2 – Wilson, Jacob M., et al. “Concurrent training: a meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 26.8 (2012): 2293-2307.

3 – Jamieson, Joel. Ultimate MMA conditioning. Performance Sports Incorporated, 2009.