Breathing is very important to life (obviously), yet very few of the athletes and general population clients that I see understand how to do it effectively. I can probably recall one person out of twenty people that I’ve assessed who has had an adequate breathing pattern. Now, the standards for breathing are out there, and it can be quantified via tidal volume, respiratory rate, and various laboratory equipment. However, my focus is purely on immediate performance in the gym and on the field.

Breathing Standard

There are many different types of standards found for optimal breathing. Some organizations identify how to best improve upon breathing mechanics by respecting the dome of the diaphragm’s position within the ribcage (termed the zone of apposition). Within this context, there are terms such as “apical breathing” and “apical expansion,” which should be defined further.

Apical breathing involves using the accessory muscles for inhalation or exhalation, but apical expansion identifies a difference by breathing more circumferentially, instead of just caudally (or towards the head).

Here, I troubleshoot and teach you specifically what to look for and how to identify if you are breathing with a faulty pattern.

Interestingly, there has been recent re-surfacing of information from the Translational Journal of ACSM in 2019 has been gaining traction, named “Effects of Two Different Recovery Postures during High-Intensity Interval Training.” In it, they cite some articles that I also draw the inspiration for this article from, along with going more in-depth into the scientific aspects of improving tidal volume, heart rate recovery (HRR), along with other measures.

Awesome to know that more and more research is supporting this (especially most recently in 2019), because this article was originally written in 2014!

Exercise Program Implications

One aspect that I’ve been inundated with for the past four years is the idea of appropriate breathing with regards to exercise. The avoidance of being within a gross extension pattern (ribs flaring) is something that I can identify with many of my athletes – since they stand for most of their time during their practice, competitions, or games, they often fall into a specific default pattern for movement and breathing. Since I’m essentially a gym rat, the application of breathing within the movement continuum can be identified within several exercises and patterns.

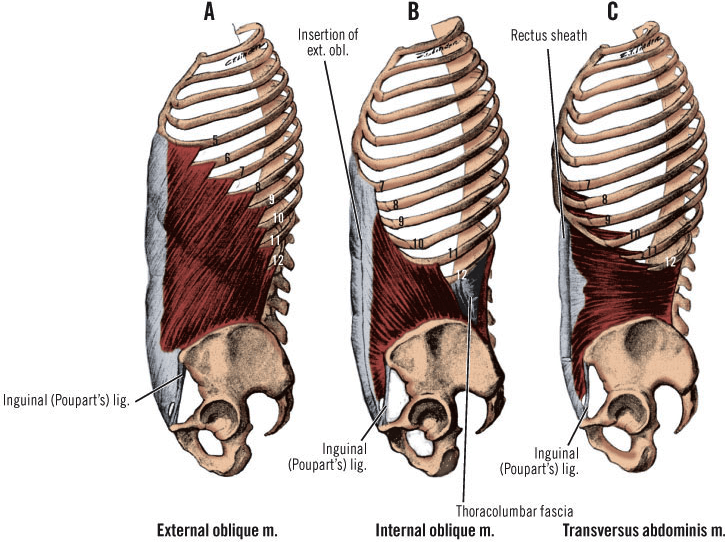

In the following examples, the internal cue of “ribs down” will be used to identify the use of internal and external obliques, as they connect on several of the lower ribs and attach to the pelvis. If the ribs are flared up in an athlete, this posture will identify the internal/external obliques as being inadequately used.

- Squatting? Bring your ribs down and brace before you squat.

- Deadlifting? Bring your ribs down and get into a neutral spine before you deadlift – otherwise you’ll be rounding at the back and using accessory muscles vs major movers to lift.

- Planks, side planks, push-ups, and chops and lifts? Better believe your ribs should be “down” and not flaring.

- One concept that is often misunderstood is the idea of exhaling on the way “up” and inhaling on the way “down”. This is a faulty method, because the answer is it depends on the exercise.

Since I’m impartial to a powerlifting method, I’d recommend inhaling, bracing, and then lifting.

On the way up, or out of the hole, I’d recommend a slight exhalation to enhance the total tension seen with intra-abdominal pressure for the lifter (not a gasp of exhalation, as this will simply just lose your tank of tension that you’ve preserved).

For other exercises however, it can be justified to breathe continuously throughout. There is no set “inhale down, exhale up” for a belly press, plank, or side plank. Promoting a continuous “breathing” component during these types of exercises will be my recommendation.

Breathing for On-Field Recovery

To take this out of context of an inside “controlled” environment such as the gym or lab, breathing has even more application in a gaming or competition type of environment. In fact, there are psychological benefits to seeing someone doubled over gasping for air, versus seeing someone sprint, cut, jump, and still stand tall towards the end of a play.

So there are two possible “incorrect” or at the very least, less advantageous ways to breathe. For our purposes today, I’ll identify these two less optimal methods for on-field recovery as “hands on head” and “hands on knees” recovery position.

The first involves breathing with your hands way up high. This was something that was told me to by anyone and everyone when you are extremely fatigued. Whether this knee-jerk reaction occurs from sprinting or running for a long distance, I think this is a telltale “sign” that you have done something exhausting. However, this also increases your chances of using the accessory respiratory muscles of the scalenes, SCMs, and upper traps.

“Hands On Head” Recovery Position

The “hands on knees” option (shown below) involves doubling over just to get a breathe. This may be attributed to extreme amounts of fatigue as well, and in reality you may be enhancing the chances of using your accessory muscles even more than the previous option.

“Hands On Knees” Recovery Position

NOTE: Some Twitter discussion sparked a clarification on the use of this position for recovery purposes. While the psychosocial aspect of this position can be correlated to the appearance of fatigue, this recovery position can also be facilitated to mechanically restore easier use of the abdominals, and posterior mediastinum for respiratory purposes. This is, of course, assuming that you don’t have a forward head posture accompanied with an upper trap shrug, as that will take you out of an “optimal” recovery strategy.

“It’s okay to be tired. It’s not okay to show how tired you are.”

Which do you think will put your body into more of a sympathetic overload: breathing using your neck muscles, or breathing using your nose, filling your lungs up slowly with air, while exhaling fully with your diaphragm?

The justifications that can be made for the following option involve apical expansion of the lungs by breathing “fully” throughout your torso, along with appropriate inhalation through the nose. This not only ensures full inhalation of the lungs when your body needs the oxygen, but also prevents the body from going into further “system overload” while shifting away from accessory respiration.

“Hands Around Stomach” Recovery Position

By placing your hands around the bottom of your waist and sides of your abs, you not only provide that psychological “aura” of unending stamina, but you can also increase your proprioception to the areas that often need filling up the most. At best, it’ll look like you’ll be flexin’ hard, bro.

- Further, by placing your hands around your hips/ribcage (where your obliques attach), you’ll be acquiring more sensory awareness within this region, which should guide your breathing into a 360° circumferential expansion.

- This is opposed to chest breathing or apical breathing, where the breath only rises upwards, but not down and around on the inhalation and exhalation.

- Increasing oxygenation of your body after a stressful activity will allow less feelings of “gasping” for air.

- If you are not “gasping” for air, you won’t have to breathe with accessory muscles.

- Since accessory muscles aren’t as profound for recovery on a mechanical and systemic level, you’ll have less anxiety during your recovery periods.

- If you have to return to play immediately following a bout of sprints, for example, you’ll be able to return to a clear-headed level of play sooner when using this diaphragmatic breathing option.

In any case, give the “hands around hips/sides of body” recovery position a shot next time you are feeling fatigued during a workout or game and you can help improve not only your psychological well-being, but also improve your recovery time as well. It would also be interesting to see if there would be an updated study on “hands on hips/sides” to see if more sensory awareness of the obliques attachments will improve upon similar biological markers that were identified in several studies!

As always,

Keep it funky.