This is an article on the 90/90 Hip Shift, and is the second part of a four part series involving the 90/90 Hip Lift and beyond. The first part may be found here:

Understanding How Your Body Moves

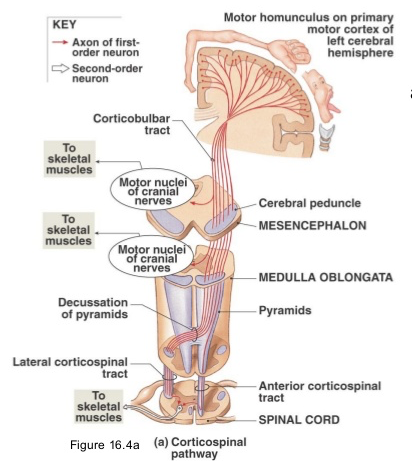

So, the brain senses and sends signals to muscles. Then, these muscles pull on bones, and if given enough proximal stability in one area, then the distal region of that same bone will begin to move. Then, the bones’ joint articulations will touch and approximate on another joint, which will allow for specific ranges of motion to be expressed.

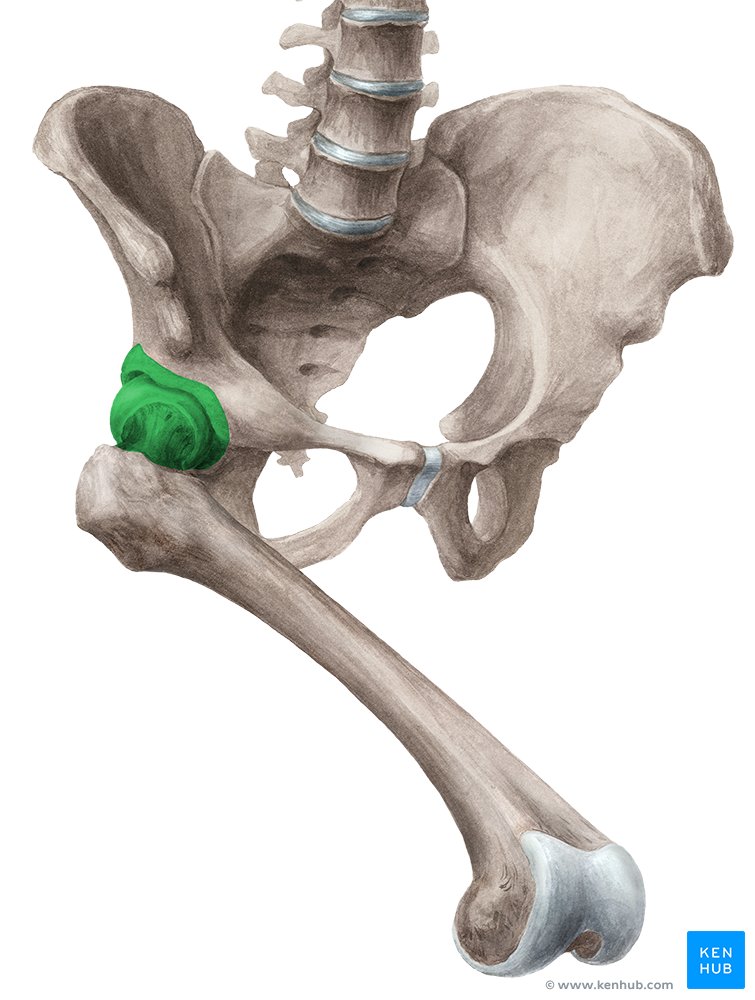

For example, if the brain sends motor signals to the hip internal rotators to move, the muscle fibers of the hip internal rotators will begin to rotate the femur within the hip. Then, once the femur reaches its end range of motion within the acetabulum, if there is more desire to move than is expressed, there may be excessive (or inefficient) movement found at the knee (where the distal femur articulates with the tibial plateau), or further in up beyond the pelvis (in the lower back, for example).

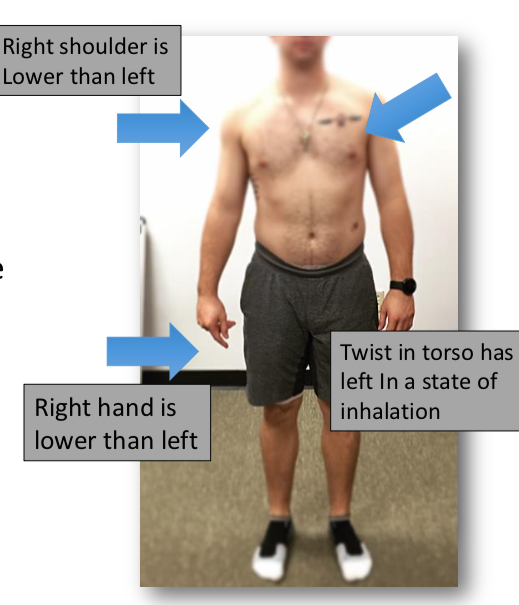

Now, extend this concept globally to the whole body, and not just at a singular joint. If your body tends to have a right sided bias, and a rotary component leaves your body with the above ROM…

…is it possible to inhibit musculature that is leaving your right shoulder with a lack of internal rotation, without directly affecting the specific area? I’d argue yes, you can.

The reason being is that your arm is simply not experiencing a lack of shoulder internal rotation, but it is also experiencing a lack of trunk rotation (to one side), a lack of hip rotation (in one side), along with possible cervical rotation asymmetries.

Further, there may even be different values found at the ankle region for supination, pronation, dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion. All these reasons could be potential reasons why there is a lack of shoulder internal rotation deficit, which could, and should be accounted for as well.

With this said, perhaps an exercise can identify how to restore trunk rotation, cervical rotation, hip rotation, and ankle motion, which will then allow your shoulder internal rotation to be restored – without even doing an arm exercise to begin with.

Your body works integratively, and it can recognize when there is greater range of motion in another area adjacent (or not adjacent) to it, which will allow your body free up movement in said adjacent area. At its simplest, this phenomenon is called regional interdependence. (1) Other models may discuss this within the context of self-organization and motor control. (2)

There are certainly many different exercises that can improve upon shoulder internal rotation via the principles of regional interdependence, neuromuscular adaptations, and motor control.

With this said, I’ll be discussing the 90/90 Hip Shift from the Postural Restoration Institute.

What is the 90/90 Hip Shift?

The 90/90 Hip Shift is another foundational exercise from the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI). Much like the 90/90 Hip Lift, the 90/90 Hip Shift is also often taught in the foundational courses from PRI, and is the next level used to help integrate the body together.

The 90/90 Hip Shift is performed in a supine position (on your back), with your feet on an elevated surface, and knees in a flexed (or bent) position.

More often than not you’ll have something between your knees, not just as a formality, but used to help feel and sense differences in position between one leg’s position, and another leg’s position.

At the end of the day, this exercise is a neurologically based exercise, that is often utilized to identify and treat biomechanical issues that arise from lower body, the lumbar spine, along with any knee issues as it relates to force absorption, along with subconscious movement (such as activities of daily living, walking, running). I bring up the subconscious aspect because by performing this activity, you don’t need to constantly monitor movements day to day, watching every movement and every activity that you perform.

Populations That May Benefit

- Athletes that utilize asymmetrical patterning (throwing, one-handedness, rotational athletes, track athletes that sprint on the track, etc)

- Individuals that are asymmetrically biased for work or in activities of daily living (drivers, individuals who carry bags on one side all day)

- Individuals that may have an injury on one side (lower body, thoracolumbar asymmetry, etc)

- Individuals that may be experiencing a lack of shoulder internal rotation

- Individuals that may be experiencing hip impingement-like symptoms with hip flexion and hip internal rotation

Purpose for Using This Exercise

So the purpose behind using the 90/90 Hip Shift is a bit different than a simple bilaterally based exercise (such as the 90/90 Hip Lift), which did not bias towards one specific side.

In this case, the 90/90 Hip Shift is an exercise that can re-orient the nervous system to account for the potential biomechanical discrepancies that may be present, and improve upon the nervous system’s ability to self-organize and locomote.

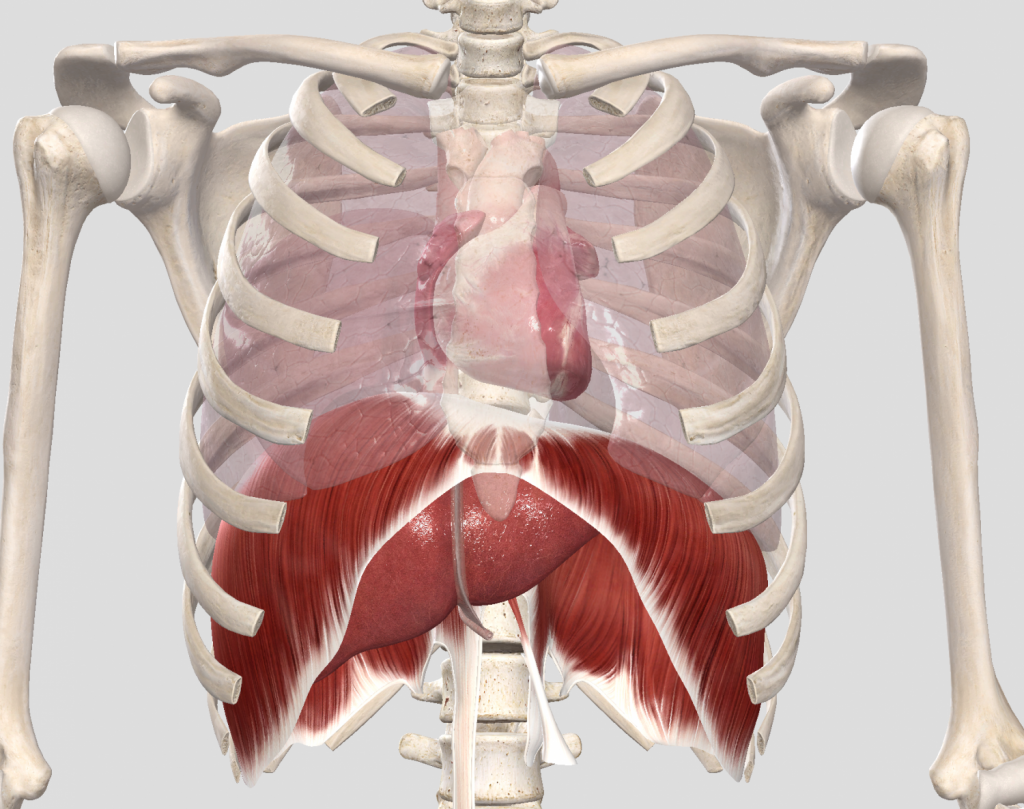

Further, much like I explained in the first article (The 90/90 Hip Lift), there are kinesiological asymmetrical differences in the right versus left side of the human body.

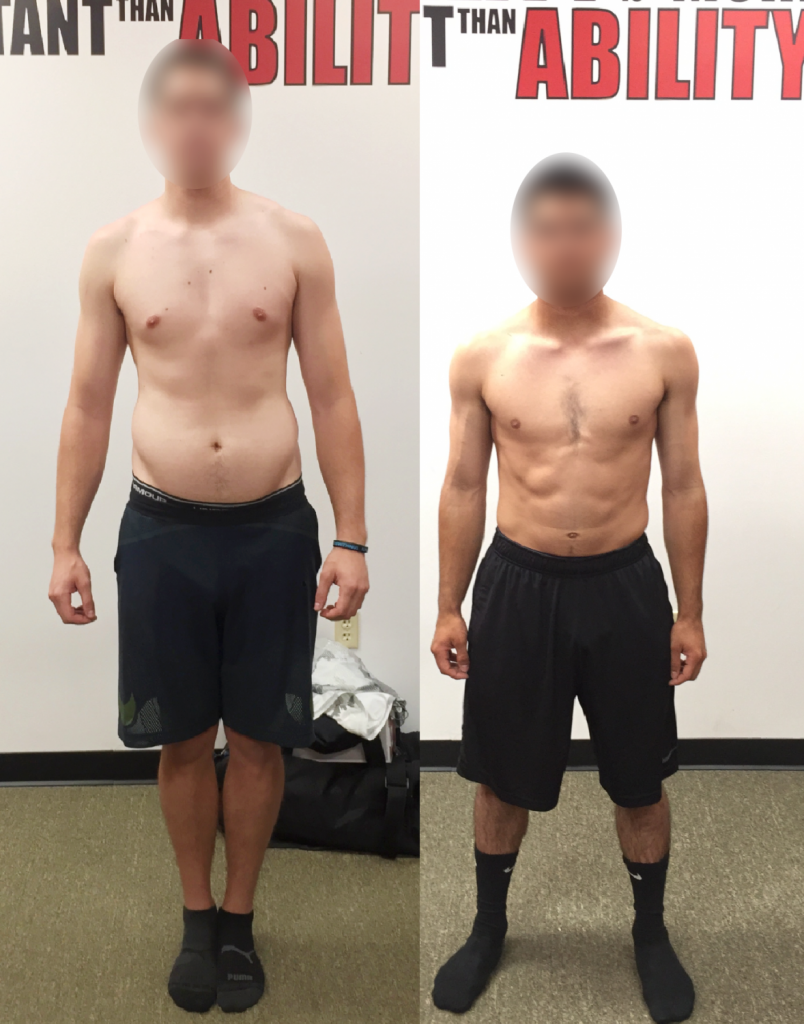

The 90/90 Hip Shift is an exercise that is aiming to improve upon this natural asymmetry in the body, prior to any further behavioral asymmetries exacerbate into an orthopedic problem. Or, in other words, this exercise’s purpose is to reduce any physical discomfort or problems brought about by this one-sidedness, and hopefully address it before any more difficult problems arise (bony impingements, capsular problems, etc).

Instructions for the 90/90 Hip Shift

PRI Instructions Verbatim:

- Lie on your back with your feet flat on a wall and your knees and hips bent at a 90- degree angle.

- Place a 4-6 inch ball between your knees.

- Inhale through your nose and exhale through your mouth, performing a pelvic tilt so that your tailbone is raised slightly off the mat. Keep your back flat on the mat.

- As you maintain a hip lift, shift your left hip down and your right hip up so that your right knee is slightly above the left.

- Slowly take your bent right leg on and off the wall so that your right thigh comes toward your chest. You should feel the muscles behind your left thigh and left inner thigh engage.

- Perform 3 sets of 10 repetitions, 1-2 times a day.

- Repeat for other side (my instructions).

Competency in the 90/90 Hip Shift

The next step involves understanding how to hold the previous movements’ lessons, and how to incorporate the next components involved with the 90/90 Hip Shift.

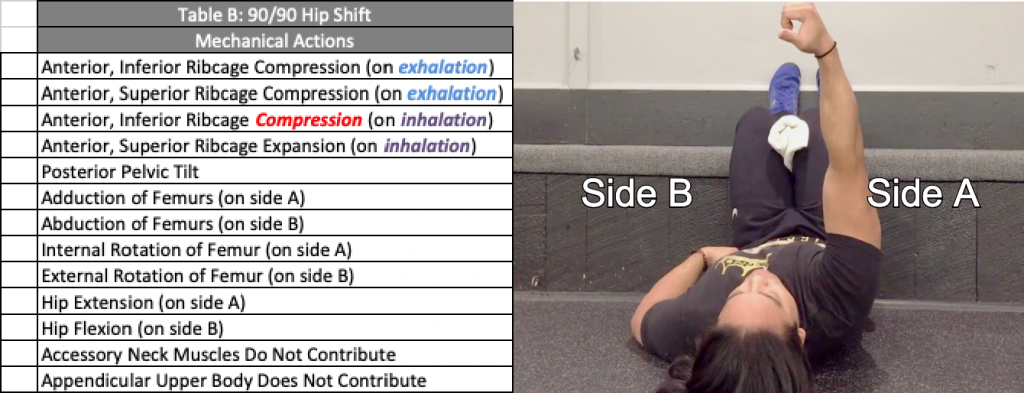

With Table B, there are roughly 13 items that need to take place before moving on. If they don’t take place, can you really say you’ve achieved an authentic 90/90 Hip Shift? Some other questions to help improve confidence in the acquisition of these motor strategies involve:

- Achieving hip adduction in one side, with concomitant hip internal rotation may further stabilize and anchor the leg (side A).

- While you’re achieving hip adduction of the femur and hip internal rotation on one side, can you also acquire hip abduction and hip external rotation of the other side (Side B)?

- Can you confidently say you’ve achieved these items (in Table B) without losing the original 90/90 Hip Lift position as well?

- Can you say you’ve achieved an appropriate zone of apposition if your accessory neck musculature helps breathing during these unilaterally based movements?

Biomechanical Reasoning

So, if a rotational athlete (baseball player, tennis player, etc) performs hundreds to thousands of rotations to improve at their sport (hitting, throwing, etc), chances are they will begin to create a body that is made for that sport. In other words, there will be soft tissue adaptations, and more likely structural adaptations, that will allow the individual to excel at the sport they are playing.

There may even be differences from dominant arm to non-dominant arm, along with ability to rotate (trunk rotation) which measures the ability for the spinal vertebrae to rotate, along with lower body contribution to performance based asymmetries found in the body. (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

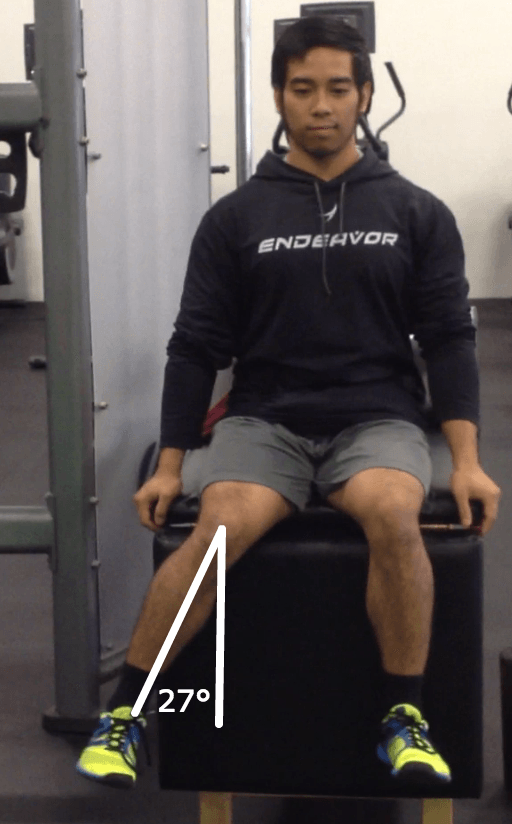

Let’s say we hypothetically have a baseball pitcher with the following upper body range of motion (ROM) values:

Right Handed Pitcher (High School/College)

- Supine Shoulder Internal Rotation (Right): 45°

- Supine Shoulder External Rotation (Right): 130°

- Total Shoulder Motion (Right): 165°

- Supine Shoulder Internal Rotation (Left): 90°

- Supine Shoulder External Rotation (Left): 100°

- Total Shoulder Motion (Left): 190°

At first glance, this may make sense – the right-sided dominance (right hand pitcher) may exhibit greater range of motion in shoulder external rotation due to pitching demands, and likewise decreased motion in shoulder internal rotation due to the eccentric control found from throwing.

You do all of the “correct” things a practitioner would do in this situation – no bench pressing, no pull-ups, no barbell back squatting, etc. This is done to prevent any biomechanical issues in the weight room from exacerbating the sports specific movement found in the field.

Further, you also pay attention to evidence based research, and understand the differences within the context of GIRD (glenohumeral internal rotation deficit), which accounts for the bony adaptations (Wolf’s Law) found through repetitive force and stress on the body. The SAID principle dictates that “the human body adapts specifically to imposed demands.” All of this holds water, because if there are structural adaptations, they will be present in the body when properly identified through passive ROM assessment.

However, what happens if there are surgeries, procedures, or techniques that have slight risk with them (eg, dry needling, manipulation, etc) that focus on improving these often debilitating or painful regions of the body, when in reality those areas are a result of this asymmetry? Is it possible to restore this asymmetry, and forego any detrimental procedures that can’t be taken back?

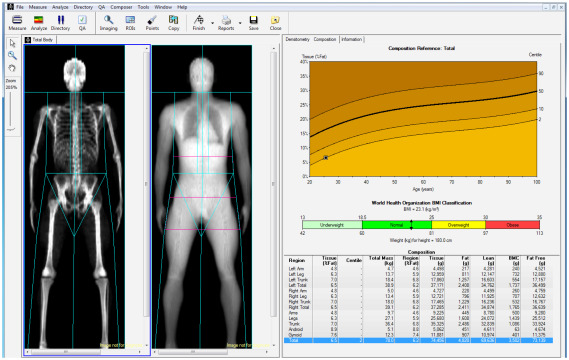

To take it to the next level, there can even be DEXA scans to identify different bone mineral density in the whole body, which, if I were to surmise, there would be greater bone density in the dominant arm and dominant leg (the left leg for right handed pitchers, athletes, etc.) (13)

Even with DEXA scan identifying differences in greater bone mass in one region versus the other, is it possible to restore neurological asymmetry despite structural asymmetry?

So, what do you do with this information? Do you simply let it go, and assume it can’t be changed? What if there is something you can do to improve upon one region of the body, in order to affect another region of the body (indirectly)?

My purpose here is to hopefully say yes, and begin to re-allocate physical stressors asymmetrically, and to stress the other side as well.

90/90 Hip Shift and the Gait Cycle

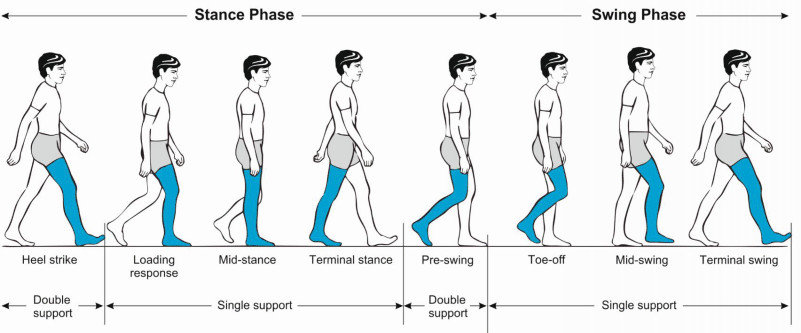

For ease of understanding the 90/90 Hip Shift, the purpose of shifting femurs and hips is reminiscent of the gait cycle, more specifically swing and stances found in the lower body.

Understanding the basics of the gait cycle will allow one to understand what is specifically going on with the 90/90 Hip Shift. Specifically, there are two phases of gait that are important here – stance, and swing. These two phases are not only evident in walking, but it is also translatable towards movements in the gym.

With respect to the 90/90 Hip Shift, there are ALSO two phases of gait. When one side is “weight-bearing” it is in the stance phase, and the “swing” phase is experienced on the other side. This is also reflective of the musculature that is synonymous with swing and stance phases of the gait cycle.

For example, when performing a 90/90 Hip Shift on the right side of the body, the foot is integrated and in a mid-stance position with the foot experiencing the windlass mechanism, along with the adductors, well adducting, and hamstrings stabilizing a pelvis on top of a stabilized foot.

This side is weight bearing, thus it is in the “stance phase of the gait cycle.”

With the left side of the body, the foot should experience a degree of supination, with concomitant left femoralacetabular (FA) external rotation.

The gait cycle involves more than just the thighs moving underneath a torso and upper limbs flailing about. Rather, movements in the gait cycle are also reflected in the…

- Thoracic region

- Pelvic girdle

- Tibiofemoral joint

- Ankle complex

The execution of the 90/90 Hip Shift is similar to the 90/90 Hip Lift, in that that the first components of the movement need to be obtained. So, if you need to teach your body how to perform a posterior pelvic tilt, you will often need to acquire that motor skill before performing the 90/90 Hip Shift, because it is a bit more nuanced than simply getting “global” motion on both sides.

The “Why” Behind Integration in the 90/90 Hip Shift

Integration on a mechanical level involves not just respecting the lower body’s contribution to the gait cycle, but also the upper body’s limbs, trunk stabilization, and acceleration of all of these pieces as well. In fact, upper and lower body limb movements are coupled (or working together) despite the upper body being immobilized in this specific study. (8)

Now, before the argument for training these movements is reduced to “this is simply the gait cycle,” understand that the body does much more than place one foot in front of the other.

With this said, the bipedal nature of the gait cycle is quite literally an evolution out of our quadruped primate ancestors. (9) There are certain features that are borne out of an evolution towards a bipedal gait cycle. These involve different depths of joint sockets, the different densities of certain bones such as the vertebrae, femurs, and tarsal bones, which all allow for greater ability to weight bear, along with many other structural items that dictate greater access to not just walking on two feet, but also the need to hold, grasp, and manipulate items with our hands.

Further, there is understanding that altering stride frequency, stride length, along with understanding the kinetic and potential energies involved with bipedal walking allows us to understand how this evolution is beneficial towards energy consumption as well. (10)

So, with all this being said, understanding everything above the pelvis (trunk and upper limb contribution) is also important towards completing your understanding of the gait cycle. (11) (12)

Performing Both Sides of the 90/90 Hip Shift

Now, I realize I made an argument for identifying asymmetry on one side of the body, particularly a right-sided asymmetry, especially those that may be involved with rotational sports. However, there is more than just a structural or kinesiological asymmetry present in our bodies, but rather there is a neurological asymmetry present with our brains and how it delivers information, and receives information as well.

With this said, there is a huge contention within those that are merely exposed to a little bit of information from PRI that when you do the 90/90 Hip Shift, or almost any asymmetrical exercise within this context, that you need to only acquire the left side of the body. I’ll address this here and now:

Acquire competency in the right side of the body first.

Yes, it is understood that range of motion that is being assessed, and it is often expressed in a unilaterally and asymmetrically biased fashion.

However, if there is “competent” control of the right side of the body, then going into femoralacetabular (FA) internal rotation, femoralacetabular (FA) adduction (among other movements), then surely you would also have adequate and “competent” control of the other side (left side) of the opposite movements – FA external rotation and FA abduction. If you don’t have authentically own a right side, then you surely don’t authentically own a left side.

So in layman’s words – you need to express range of motion in your right side, before continuing onto the left side of your body. The right side of your body may have the capacity to express certain ranges of motion, but this may be only due to the biological differences that are found in your body, not through willful motor competence.

To be clear, an individual who is expressing an asymmetrical pattern (such as right-sided or right dominant motor control or ranges of motion) is often moving secondary to a neurological and asymmetrically oriented pattern found in the brain. They are neither in control of their right nor left side – but rather they are moving without appropriate executive control of their body. To “own” both sides, you’ll need to first master one side – and by mastering one of these sides, you will be that much closer to owning the next side.

In Review

- Understanding that there are asymmetries in the body, regional interdependence, among other principles, allows a practitioner to improve ROM in one region of the body, without necessarily affecting area directly.

- Athletes and other individuals who use one side consistently and constantly may experience a greater expression of these asymmetries via ROM throughout the body.

- This exercise, among many others, is aiming to replicate the biomechanical, musculoskelatal, and neurological stresses that are experienced in the gait cycle.

- Re-orienting the body’s position can help self-organize one region of the body in order to reduce stress and improve degrees of freedom in another region of the body.

- It may be possible to identify these asymmetries through bony adaptations through a DEXA scan.

- The nature of walking with two limbs (bipedal) is borne out of an evolutionary development, and its processes can reflect metabolic efficiency, along with greater ability to manipulate and grasp tools, along with communication.

- Acquiring one side of the body on a neuromuscular level may be more advantageous due to the natural bias that is in place from kinesiology – aka acquisition of the right side of the body.

Admittedly, this is a lot of information to digest. But after taking close to twenty Postural Restoration Institute courses, this is the bulk of reasoning that I can offer when speaking about the 90/90 Hip Shift, and postural (and neurological) asymmetry.

Stay tuned for the next article, where I’ll go over integration beyond biomechanics in the 90/90 Hip Shift.

As always,

Keep it funky.

References

1 – Wainner, Robert S., et al. “Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come.” (2007): 658-660.

2- Davids, Keith. “The constraints-based approach to motor learning: Implications for a non-linear pedagogy in sport and physical education.” Motor Learning in Practice. Routledge, 2010. 23-36.

3 – Robb, Andrew J., et al. “Passive ranges of motion of the hips and their relationship with pitching biomechanics and ball velocity in professional baseball pitchers.” The American journal of sports medicine 38.12 (2010): 2487-2493.

4 – Laudner, Kevin, et al. “Thoracolumbar range of motion in baseball pitchers and position players.” International journal of sports physical therapy 8.6 (2013): 777.

5 – Freehill, Michael T., et al. “Glenohumeral range of motion in major league pitchers: changes over the playing season.” Sports health 3.1 (2011): 97-104.

6 – Ryan, Gary J., and Andrew J. Harrison. “Technical adaptations of competitive sprinters induced by bend running.” New Studies in Athletics 18.4 (2003): 57-70.

7 – Roetert, E. PAUL, TODD S. Ellenbecker, and SCOTT W. Brown. “Shoulder internal and external rotation range of motion in nationally ranked junior tennis players: a longitudinal analysis.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 14.2 (2000): 140-143.

8 – Kuhtz-Buschbeck, Johann Peter, and Antonia Frendel. “Stable Patterns of Upper Limb Muscle Activation in Different Conditions of Human Walking.” Brazilian Journal of Motor Behavior, vol. 9, no. 1, 2015, doi:10.20338/bjmb.2015-0005.

9 – Ceunen, Erik, et al. “On the Origin of Interoception.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 7, 2016, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00743.

10 – Vaughan, Christopher L. “Theories of bipedal walking: an odyssey.” Journal of biomechanics 36.4 (2003): 513-523.

11 – Nott, Cameron R., et al. “All joint moments significantly contribute to trunk angular acceleration.” Journal of biomechanics 43.13 (2010): 2648-2652.

12 – Goudriaan, Marije, et al. “Arm Swing in Human Walking: What Is Their Drive?” Gait & Posture, vol. 40, no. 2, 2014, pp. 321–326., doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.04.204.

13 – Ireland, Alex, et al. “Upper limb muscle–bone asymmetries and bone adaptation in elite youth tennis players.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 45.9 (2013): 1749-1758.APA