There are tons of benefits to exercising and beginning a strength training regimen if you’re pursuing a dance as an art, career, or hobby.

Plenty of dancers believe that in order to improve their craft, they should only dance more and more. While there is certainly plenty of merit to this notion, and specific technique does play a role within the context of being noticed early on during high school for dance academies and universities, there are some physiological benefits to training for improved performance.

Improved Muscular and Ligamentous Strength

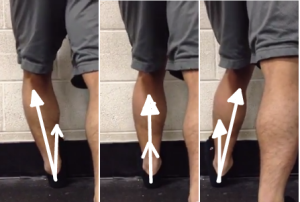

It is often necessary to get into positions that your body is not normally readily available to bend, twist, and rotate into as a dancer. By performing various stretches over and over, the passive restraints that are involved with complex joints like the hip joint and shoulder joint may be overstretched.

The elastic quality of your muscles allows some give and take – there is pliability when you move into and out of certain positions. This can be distinguished between the passive restraints such as your ligaments, because there is not as much restoration of these elastic properties if these structures are overstretched.

Many different physical therapists such as Gray Cook have notably said to not bring a mobility solution to a stability problem. What can be interpreted from this statement is that if you have excessive hip mobility, there is an obvious lack of hip stability. Stretching further into these imbalances for the mere fact that there is a sensation of tightness may not be the correct solution to bring to the table. The stability I am referring to involves specific strength training exercises. In this example, performing a reverse lunge with sufficient weight can will require both stability AND mobility.

Improve Force Production

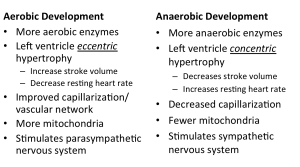

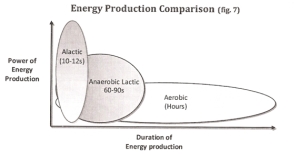

Sometimes getting bigger is not always the end goal for dancers. However, this should not deter dancers from improving their ability to produce force in a productive manner.

Force production helps with jumping.

Jumping is an example of an output that requires a large amount of force production.

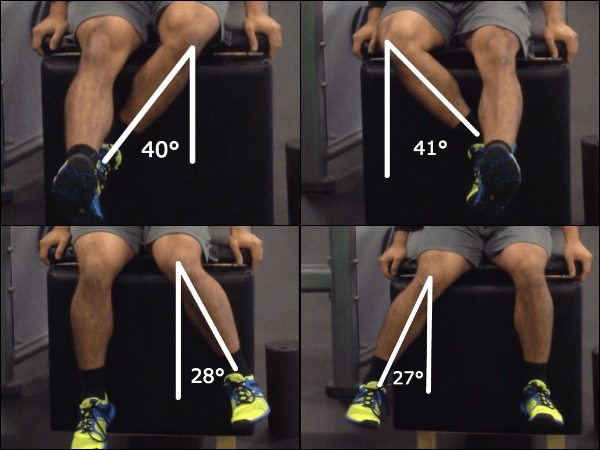

When more force is produced (through physiological adaptations from an exercise program) there likewise needs to be more absorption of force after you land from such a tall height.

The higher you are, the more ability you will have to rotate (if you stay in the air longer). When you land, hopefully land with gracefulness that displays appropriate force absorption!

While there are plenty of factors involved with improving what is known as ground reaction force when jumping and landing (either on two legs or one leg), if there is an apparent weakness or previous injury, the act of jumping will stress the body, and the path of least resistance will be discovered overtime, if not acutely.

Improve Time to Recovery from an Injury

As a dancer myself, I know the heart sinking feeling of rolling an ankle (multiple times), or tweaking an adductor, or having a weird knot in my back prevent me from doing what I love the most – dancing.

Bronner et al displays that with an appropriate timeline and exercise regiment, time to return for dancing improves greatly. Further, over 60% of the injuries reported during this time happened to be lower extremity related – that means 6/10 injuries in a troupe were hip or knee oriented. Add in about a 20% injury rate on ankle and foot injuries, and you have over 80% of injuries merely being reflective of just the lower half of the body.

Now, the real question is, why do you have to be a professional dancer to reap the benefits of a comprehensive exercise program? Certainly having a physical therapist on hand at every beck and call when something begins to hurt let alone itch is one benefit of being in a professional dance company, such as the one described in the study.

However, you don’t always have to lose sight of the big picture, which if you’re like me, is performing for an artform that you love.

With all this in mind, I have a program that might be the right fit for you.

With the Modern Strength Movement, found on the Fitocracy platform, you get the benefit of working out with a community of people, improving your strength and muscle mass goals, along with improving the habit of exercising to maintain performance for dancing.

If this sounds like something that you can benefit from, please read on ahead to the Frequently Asked Questions portion of the page!

As always,

Keep it funky.