Aerobic conditioning often brings about a knee-jerk reaction to thought processes of running long slow distances.

The fitness industry has gone back, forth, and back again as to why “long slow distance (LSD) running” is bad for you.

I’ve even written an article as to why running is “bad” for bboys. Looking at only mechanics of running versus three dimensional movement is a bit short-sighted of me, and I apologize for the lack of applied information.

However, aerobic fitness as a concept is important.

- As a concept, aerobic fitness will help to improve nervous system functioning.

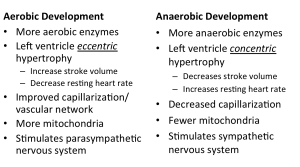

- It will also help to improve cardiac functioning (improvements and increases in aerobic enzymes and left ventricle of the heart).

- Lactate threshold levels are realized sooner if the body’s metabolism is not functioning from an aerobically optimized system.

When learning and adapting newer information, I have one main thought in my head:

Will this benefit dancers?

And the answer to this question of whether or not aerobic fitness will help is yes – aerobic fitness is extremely important for dancers.

By improving your aerobic conditioning, and improving on the body’s exchange of oxygen, you can exhibit less fatigue, last longer throughout battles, and even more extrapolated, you can improve your ability to learn new combinations and movements by the simple notion that if you are fatigued, you won’t be able to practice as intensely or for as long.

Photo Credit: RobertsonTrainingSystems.com

To take a step outside of the context of strictly just breakdancing, aerobic fitness is important for dancers of all types as well.

How? I’m so glad you asked.

Improving aerobic fitness can improve recovery.

Allow me to put this in a more realistic context. Imagine you are traveling from city to city, or you are performing night after night with no days off between rehearsals and performances.

Stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system is helpful for rest and digest mechanisms.

Increasing and improving cardiac parameters related to a more optimized aerobic system will allow more blood to flow with less cost to the system as a whole – more transactions with less cost.

This is opposed to enhancing your anaerobic, or more specifically the alactic/lactic energy systems, where there is only a finite amount of energy stores that will cost a lot more in terms of energy for the body to utilize.

How can I improve my aerobic fitness?

Money question there, young buck.

However, this is both a little more complicated than just running for hours every day. Sometimes it is as simple as reducing the amount of conditioning you are currently doing. The name of the game when it comes to dishing out advice online is that it depends, because everyone is different and will respond differently to exercise prescriptions.

Observations with Respect to Aerobic Fitness and Movement

My aerobic conditioning is lacking. For the past 3-4 months I’ve been tracking my heart rate whenever I session with people or whenever I’ve been on my own.

- Power moves bring me up to an exceptionally high heart rate very quickly.

- Even more obvious – footwork, toprocks, transitions, and combination movements result in lower heart rate numbers due to less demanding tasks (when compared to powermoves often seen in bboying).

So with this, I have a few suggestions for other dancers to try.

1. Buy a heart rate monitor and start seeing when you go over a certain threshold.

There are many ways to standardize your heart rate numbers, and “see” where you are in comparison, but if you go running, and utilize the running data as a means to set a standard for where your bboying conditioning should be, then we are already setting you up at a lower standard.

One quick way to do this is to perform your most intensive set, or footwork, or go all out with whatever move set you choose while wearing and tracking your heart rate.

- Afterwards, see how long it takes for you to return to a heart rate of 130 bpm.

- Record this time, and remember your move set.

2. Front load power moves in the beginning of the session.

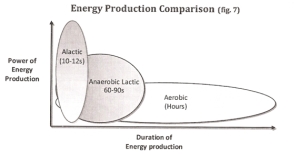

There is a finite window of opportunity with which to practice, due to physiological demands from ATP and PCr energy stores being the drivers in these large movement patterns.

Photo Credit: 8 Weeks Out

Also, the body’s nervous system has only so much in the “tank” before it gives – so by front loading your choice of movements to work on in the beginning, you are more likely to perform these movements cleanly, while simultaneously improving your capacity to learn and string movements cleanly together.

Basically, by being less fatigued you are more likely to improve your capacity to move more and move better.

Performing movements under high levels of fatigue may pre-dispose you to a host of systemic issues, namely utilizing synergistic muscle groups as prime movers, when they should be stabilizers, otherwise known as synergistic dominance.

This leads to my next point.

3. Perform movements cleanly, and once you get sloppy, stop.

If you begin to drop in intensity, or it takes longer than a set number of seconds/minute(s) to recover your heart rate, then you should move on to the next task.

I have the ability to discuss heart rates during power moves because I literally had a heart rate monitor on when practicing power moves. Sometimes it took me 2 to 3 minutes to recover from a heart rate of 196 to 130 BPM. If I can make an assumption that someone will have a greater aerobic fitness level than me, then it should take that person less than 2 minutes to restore to an acceptable percentage of heart rate max.

Hopefully at this point, you understand the concept that there are wanted variables and unwanted variables when training. Reaching technical failure on a movement is a largely unwanted variable.

4. Train footwork and transitions to stay within a heart rate of 130 to 150 BPM.

Call this mental conditioning, but next time you practice footwork, give this a try on your off days. By staying within a certain pre-defined heart rate (the 130-150 BPM is an assumed target heart rate – each individual will have fluctuations above and below these levels), you are more likely to stay within a specific range of functioning.

Why?

Well, I’m always looking to see if things will transfer to the task that is necessary.

In this case, bboying is the name of the game.

So if you can perform your sets, footwork, and other dancing at a lower heart rate than previous sessions, I’d like to imagine your economy of movement is improved.

Basically you’re more efficient.

I’d say you’re relatively inefficient if your heart rate is at 190+ during footwork for 2 minutes at a time.

5. Recovery between sets is important, so be cognizant of your work:rest ratios.

If you perform back to back sets, chances are you will be at a high heart rate for a long time. Literal physiological power output will likely decrease past a certain number of seconds (8 seconds is the an important time to remember, as this is when the alactic energy system is primed for contributing.)

I’ve timed bboy sets, watched hundreds if not thousands of battles by this point, and I’ve competed as well, all to make an observation that more often than not, many higher level bboys utilize a timeline of about ~15 to 30 seconds of powermoves, footwork, and dancing to get their point across.

Any more time than that, and the message you are trying to convey may not come across as well due to fatigue.

Obviously, performances will have a different set of demands, as they often range anywhere from ~2 minutes to 60 minutes+ of high performance energy!

—

For those interested in more application of energy systems training to dancing, read on ahead as I’ve attached some interesting items from Mike Robertson and Joel Jamieson respectively.

Further, if you’re interested in learning how to take it to the next level of dance, please sign up for my newsletter, and/or pass or share this info along using the easily available buttons at the bottom of this post. I would appreciate it!

As always,

Keep it funky.

Further Reading

Robertson Training Systems – 10 Nuggets, Tips, and Tricks on Energy System Training

8 Weeks Out – Research Review: Energy Systems, Interval Training, & RSA

8 Weeks Out – Truth About Energy Systems (VIDEO)